A research team from Lehigh University is spearheading a novel approach to tackling antibiotic-resistant bacteria. This approach would essentially “trick” bacteria into revealing vulnerabilities in its cell wall, a jacket-like structure that surrounds it, so new drugs can be developed to defeat the bacteria.

Antibiotic, or antimicrobial, resistance is a growing problem around the world. An estimated 23,000 American lives and 700,000 lives worldwide are lost each year as a result of bacterial infections resistant to current antibiotic treatments.

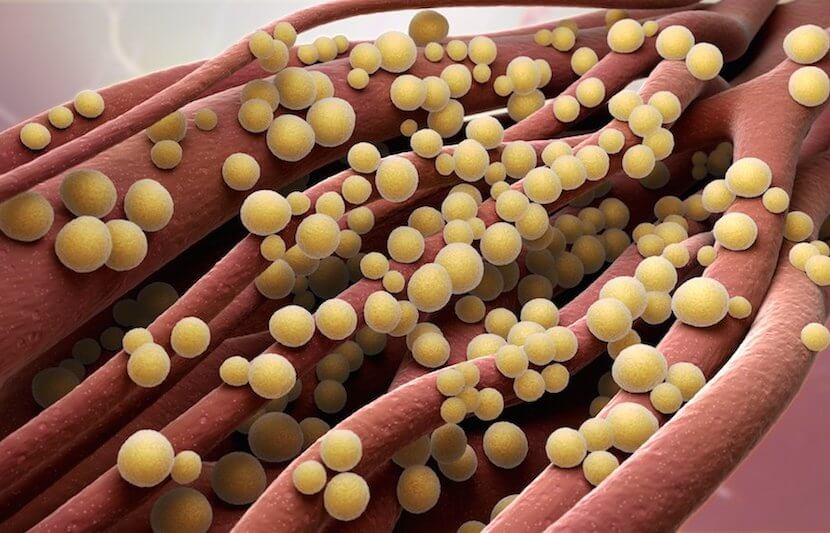

Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacterial cells create ways to adapt and evade the drugs designed to kill them. One way bacteria is able to do this is by making changes to the cell wall.

The new research is led by Marcos Pires, an assistant professor at the university’s Department of Chemistry, who has received a five-year $1.94 million MIRA grant (Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award) to pursue his unique approach to uncover these cell wall changes.

Under this approach, Pires and his team induce live bacteria to absorb synthetic cell wall fragments modified with reporter units, which essentially tricks the bacteria into revealing where its cell wall is most vulnerable.

By using these synthetic cell wall fragments, the researchers are given great flexibility for installing reporter handles that allow them to observe how bacteria adapts to the challenge of antibiotics.

“By imaging where, when, or how the alterations occur, we get an unprecedented view into how drug resistance emerges,” Pires said.

One of the researchers’ goals is to identify the cell wall components that bacteria need to successfully adapt, and eventually find ways to inactivate or circumvent them.

“What we can hope to do is to learn the weakest spot within their escape of the drug being administered to find a way to re-potentiate out antibiotics,” said Pires.

Another aspect of the research includes learning more about the way bacteria constructs new cells. For infections to take hold, bacterial cells need to grow and divide, a process known as the “bottleneck” step. This process means, new cell walls must be produced inside the cell and then transported outside of it.

Pires and his team will use their technique and attempt to understand this process to discover how bacteria may alter this step to become resistant to antibiotics.

“Our ultimate goal is to get a more comprehensive understanding of the biology related to bacterial cell walls so we can understand what tools or mechanisms bacteria have in their disposal to get around our antibiotics,” he said. “With this information, we imagine that we can better target drug discovery efforts in the future or perhaps reveal drug targets that were previously unexplored.”