For many college students, the thought of having to take a physics class to fill a science requirement is a daunting task.

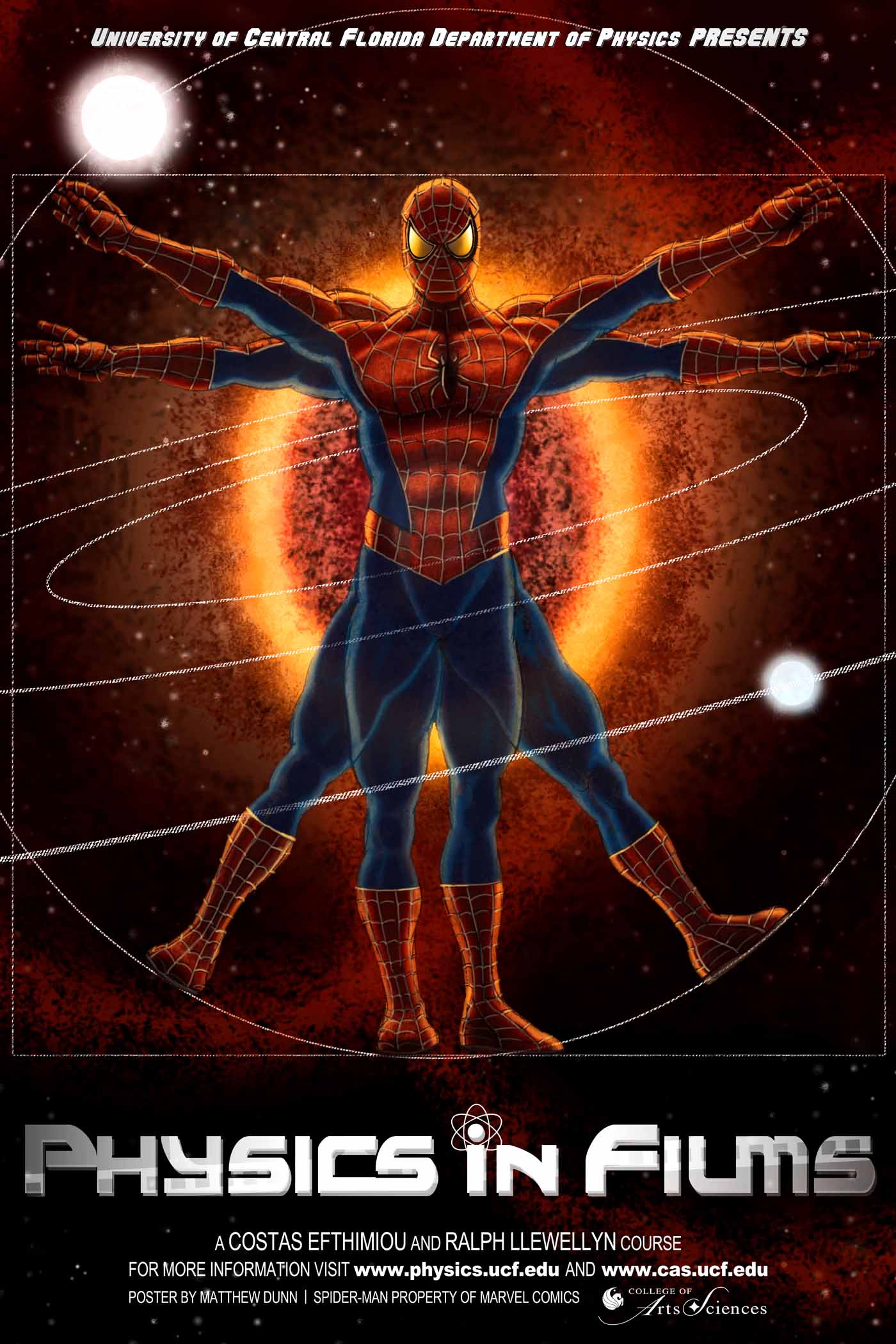

Recognizing this, Costas Efthimiou, an associate professor of physics at the University of Central Florida, is working to eliminate his students’ fear of science by teaching it through film.

In his class, Physics in Films, students learn the ideas and laws of physics by evaluating scenes in science fiction, thriller and superhero movies — remindful of the TV show Mythbusters.

Recently, Efthimiou proved the plausibility behind Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson’s epic leap off a construction crane into a building in the new movie “Skyscraper.”

“Everyone’s initial response was to ridicule the feat. My initial reaction was along that direction too — that is, to condemn the scene as impossible by physical laws,” said Efthimiou.

“However, when I teach my students physics, I always tell them that science is objective and should not allow their feelings to dominate over reason. They must verify scientifically any claim. So, I sat down to carry out the calculation and verify that there was no way that the hero could do the jump. To my surprise, the physical laws were allowing a window of opportunity. Therefore, either the director was lucky or had done his homework.”

Calculations behind the “Skyscraper” jump

Every scene in Efthimiou’s class is chosen for its science content and popularity. He chooses extraordinary scenes because they captivate the audience and give him an easy and intriguing way to explain physics.

In this recent case, Efthimiou estimated the crane to be around 20-meters long, which would allow a person to reach a horizontal speed of 20 miles-per-hour, or nine meters-per-second.

He found that if the human also reaches a vertical speed between 3.667 meters per second and 5.467 meters per second, the jump is humanly possible.

However, Efthimiou notes that the horizontal and vertical speeds needed to land this jump would have to be comparable to a professional basketball player and a professional sprinter.

“There are a number of factors working against our protagonist in this scenario: his age, psychological stress, not having proper running shoes, not having past training for this particular jump, to name a few,” Efthimiou said in a statement.

“However, given the character’s peak physical conditioning, professional discipline, mental strength, personal motivation and determination, the laws of physics assert that he has a real shot at making this jump.”

Physics in Films class

This creative method of teaching has made the course a favorite among students.

“The movies change the dynamics and make the class way more desirable,” said Efthimiou.

“Instead of having abstract science discussions and homework, the students learn science by discussing the science of selected movies and scenes. The movies makes the students feel more comfortable and, as a consequence, change their attitudes to be much friendlier towards science. In turn, this facilitates their learning.”

A typical lecture in the class is not much different than that of any other introductory physics course that Efthimiou teaches.

“The ideas and laws of science have to be explained,” he said.

The only difference is, in Physics in Films, Efthimiou uses popular scenes to introduce ideas, explain the laws and discuss applications.

For example, when introducing momentum conservation, he shows the class a clip of a gun — or something else — backfiring, and they will write down the mathematical law.

Then, the class will look at another video from a scientific documentary of, for example, a rocket taking off to further verify the law, explained Efthimiou.

“Finally, we will start looking in scenes selected from movies and discuss if the director took the law into account,” said Efthimiou. “Such scenes would be Cyclops (the X-Man) emitting a ray from his eyes, a rocket hitting a car which explodes and is sent up in the air, a bullet hitting a human target who is then pushed violently, etc.”

Almost every film scene has some sort of relevance in science, but Efthimiou makes a point to only choose scenes he knows his students will be interested in.

“Scenes which provide great suspense, elevated interested and unexpected possibilities are the most useful,” said Efthimiou.