A new study on fruit flies found that alcohol causes cravings by disrupting a memory formation pathway and changing proteins expressed in neurons — which may explain why alcohol addiction is so prevalent in humans.

Researchers at Brown University used fruit flies as a model for the study because the molecular signals involved in forming flies’ reward and avoidance memories are similar to those found in humans.

The research is published in the journal Neuron.

The study

The researchers wanted to understand the relationship between substance abuse and reward, and why people continue to crave drugs and alcohol even when they’re known to have adverse side effects.

To do this, they decided to focus on how alcohol affects the memory.

“We were interested in understanding why memories for sensory cues, like dim lighting in a bar, the bouquet of a favorite wine, or the feel of a glass in your hand, are so long-lasting. These memories can trigger cravings for alcohol, and little is understood of the molecular biology underlying them,” said Karla Kaun, an assistant professor of neuroscience at Brown University and senior author on the paper.

“Our rationale was that if we could understand the mechanisms underlying these memories, we would have a better understanding of how cravings happened, and potentially discover new ways to treat cravings.”

Since fruit flies have only about 100,000 neurons, as opposed to over 100 billion found in humans, the researchers thought they would be a perfect small-scale model to test their theory.

To conduct the study, they used genetic tools to turn off key genes while training the flies on where to find alcohol, allowing them to see what proteins were required for reward behavior.

The findings

The researchers found that one of the proteins responsible for the flies’ craving for alcohol is Notch, a highly conserved gene that exists in animals. Notch1 in humans is the most similar protein found in flies, explained Kaun.

Notch is considered to be the first “domino” in a signaling pathway involved in embryo development, brain development and adult brain function in humans as well as animals.

This domino effect of a molecular signaling pathway means that when the first domino falls, it triggers more and more to follow.

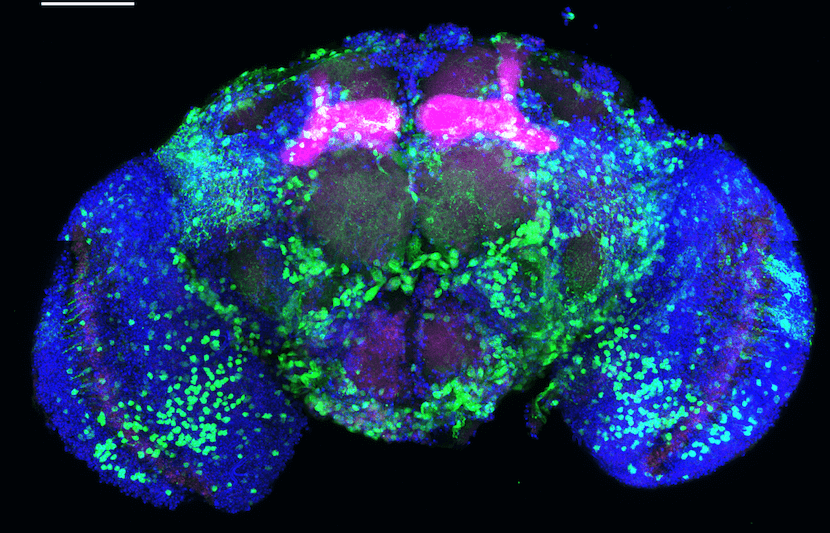

Image: Kaun Lab/Brown University

Another domino affected by alcohol consumption is a gene called dopamine-2-like receptor, which produces the “feel good” neurotransmitter known as dopamine.

“The dopamine-2-like receptor is known to be involved in encoding whether a memory is pleasing or aversive,” Emily Petruccelli, a postdoctoral researcher who led the research as a postdoc researcher at Brown and is now an assistant professor at Southern Illinois University, said in a statement.

Alcohol disrupts this memory pathway to form cravings.

But, in this case, the researchers found that alcohol didn’t cause the dopamine receptor gene to turn off or on, or even to increase or decrease the amount of the protein produced. Instead, they found that alcohol changed the version of the protein produced by a single amino acid “letter” in a key area.

“First, it’s critical to understand that genes do get turned on and off during memory formation, and by alcohol consumption,” said Kaun. “This means that the proteins in your memory circuits are changing as memories for the intoxicating effects of alcohol are being formed. Genes can have many different products, depending on how they are transcribed from a gene to RNA or translated from RNA to protein.”

These different forms can have different functions in the cell, Kaun explained. They might get localized to different areas of the cell, or they might even activate different enzymatic pathways.

“It’s critical to understand which gene products are being produced because they can change the function of the cell, potentially affecting the activity of a neural circuit, and thus affecting how a memory is being formed or remembered.”

Translating to humans

The researchers don’t know if alcohol affects the human brain the same way it activates Notch in fly memory circuits, but since the receptors are so highly conserved, the study suggests that it very well might translate in the same way, explained Kaun.

Additionally, the researchers are investigating reports of alternative splicing in the brain of human patients with alcohol disorder.

“We are currently investigating how Notch activity changes with activity of memory circuits, and looking at the functional consequence of alternative splicing in memory circuits,” said Kaun.

“We are intrigued about whether the alternative splicing of key genes persistently affects memory circuits in such a way to change future decisions about reward.”

The team is also continuing its work by studying the effects that opiates have on the same molecular pathways.

Understanding how alcohol affects memory formation could ultimately give insight on how best to treat patients recovering from alcohol addiction, according to Kaun.

“Memories for sensory cues associated with being intoxicated are extremely long-lasting and can trigger cravings in those trying to recover from alcohol use disorder,” she said.

“If we understand more about the neural and molecular mechanisms underlying these cravings, we will gain a deeper understanding of why cravings happen and what might be the best ways to treat them to prevent relapse.”