Income inequality is growing, not just in the United States but in other parts of the world.

There is also the fast-approaching threat of job loss caused by innovation in automation and artificial intelligence.

To address these challenges, policymakers will have to come up with a viable solution.

Could universal basic income (UBI) — a type of program in which governments regularly and unconditionally provide a sum of money to all citizens — be the solution?

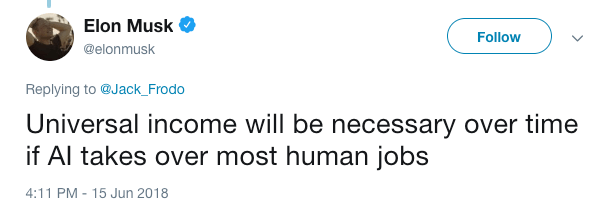

Proponents of UBI, a group that includes prominent economists, entrepreneurs, and tech leaders like Tesla founder Elon Musk and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, think so.

Yet even as governments across the world — including some American cities such as Stockton and Santa Monica in California — experiment with UBI, there is still little known about the potential consequences of such a program.

That’s where the Stanford Basic Income Lab comes in. Led by Juliana Bidadanure, an assistant professor of philosophy in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences, this pioneering program will help educate both policymakers and the public.

An uncertain future

UBI is not a new idea. The concept has been around since at least the 18th century, when Thomas Paine proposed a form of UBI, which he called “ground rent.” More recently, the idea has been proposed by reformists like Martin Luther King as well as conservatives like free-market economist Milton Friedman and ex-president Richard Nixon.

But UBI was never seriously considered in policy circles until recently. In the past few years, the idea has come back in full force and governments across the world have started UBI pilot programs and experiments.

So why the recent interest?

Rapid advances in the fields of automation and AI threaten to reduce the need for human labor in many fields. By some estimates, automation could put around half of total U.S. employment at risk. Jobs that require low-skilled labor, such as truck driving and food service, could disappear almost entirely.

Automation could be even more disruptive in developing countries. According to research conducted by the World Bank, automation could threaten 69 percent of jobs in India and 77 percent in China.

UBI has been floated as a means to alleviate the disruptions to the economy and society that automation is predicted to cause. Some of the biggest proponents of UBI come from the tech industry, including Musk and Zuckerberg.

“Universal income will be necessary over time if AI takes over most human jobs,” tweeted Musk.

Others have suggested that a UBI could provide a more efficient and direct alternative to means-tested welfare programs. UBI supporters contend that such a program would serve the same function of these programs while reducing the need for an extensive and expensive bureaucracy. Because UBI is universal, it would also eliminate the so-called “welfare trap,” in which welfare recipients are disincentivized from pursuing a higher wage at the expense of welfare payments.

So UBI is an intriguing idea, but not one without its skeptics. The idea raises challenging practical and philosophical questions. How would a UBI be funded? How much money would each individual be given? Will a UBI discourage people from entering the workforce?

“What is exciting about basic income is that it forces us to think hard about what we owe each other,” Bidadanure said in a statement. “We do need more evidence for what happens when a particular form of UBI gets piloted. But what’s as important as that data is the opportunity to spark more conversations about the present and future of work.”

Experimenting with basic income

Since Stanford’s Basic Income Lab was founded in 2017, the program has worked to bring some much-needed data to the discourse surrounding UBI.

In November 2018, the lab published a toolkit, or guide, for creating UBI pilot programs for city leaders throughout North America. Entitled “Basic Income in Cities,” the toolkit contains information about the most effective and ethical practices for basic income experiments. It is also paired with a list of current North American basic income projects.

The toolkit provides a history of UBI as a concept and details some of the UBI experiments that have already taken place in Finland, Kenya, India, Namibia and Canada.

The toolkit also gives recommendations for policymakers putting forward UBI pilots. It provides suggestions on technical issues — the best way to disperse funds to recipients, for example — and on more general concerns — how to boost the impact of the program through complementary programs, how to communicate with media about the program, etc.

The lab is also currently putting together an online “map” of UBI research. The map, scheduled to be released in 2019, will be the first comprehensive online resource for all existing information about UBI. The map will compare arguments for and against basic income with empirical evidence derived from real-world pilots and experiments conducted around the world. Like the toolkit, the map is designed to provide much-needed clarity to the debate surrounding UBI.

“The online map is the first step for us in identifying the questions that have already been answered related to UBI,” Bidadanure said in a statement. “If we better understand what the research gaps are, we’ll be in a better position to advise experimenters to ensure new pilots to help increase the evidence base.”

Fresh ideas for a changing world

Bidadanure became interested in the concept of UBI out of frustration with the debate regarding financial assistance for the poor in her home country of France.

“I grew increasingly frustrated at how politicians of mainstream parties were attacking existing benefits and public assistance in general for supposedly encouraging free riders,” she explained in a statement.

“The situation felt very stuck, and it also felt like unnecessary demonization. That’s when I realized that UBI could help the discussion. Because it’s universal and unconditional, the poor would be less easily stigmatized and the working people would be be less likely to resent ‘benefits scroungers.’ ”

Indeed, UBI has the potential to shift the discourse surrounding government financial assistance. The idea defies a traditional left-right analysis, and as a result, has attracted strange bedfellows, from hard-line capitalists to outright socialists.

Serious consideration of a UBI would also bring forth a new debate about the concept and function of work, but if the technological revolution truly does bring on a post-work society, it is a conversation we will need to have. It is of particular importance to rising generations of students and young professionals whose future employment prospects could depend on the planning that governments and private organizations do now.

“What is the value of employment? What counts as a contribution?” Bidadanure asked. “We need to have those conversations more than ever. And basic income experiments are a way to fuel those conversations.”