Environmental activists are teaming up with fresh faces in Congress to advocate for a Green New Deal, a bundle of policies that would fight climate change while creating new jobs and reducing inequality. Not all of the activists agree on what those policies ought to be.

Some 626 environmental groups, including Greenpeace, the Center for Biological Diversity and 350, recently laid out their vision in a letter they sent to U.S. lawmakers. They warned that they “vigorously oppose” several strategies, including the use of carbon capture and storage – a process that can trap excess carbon pollution that’s already warming the Earth, and lock it away.

In our view, as a political philosopher who studies global justice and an environmental social scientist, this blanket opposition is an unfortunate mistake. Based on the need to remove carbon from the atmosphere, and the risks in relying on land sinks like forests and soils alone to take up the excess carbon, we believe that carbon capture and storage could be a powerful tool for making the climate safer and even rectifying historical climate injustices.

Global inequality

We think the U.S. and other rich countries should accelerate negative emissions research for two reasons.

First, they can afford it. Second, they have a historical responsibility as they burned a disproportionate amount of the carbon causing climate change today. Global warming is poised to hit the least-developed countries, including dozens that were colonized by these wealthier nations, the hardest.

Consider this: The entire African continent emits less carbon than the U.S., Russia or Japan.

Yet Africa is likely to experience climate change impacts sooner and more intensely than any other region. Some African regions are already experiencing warming increases at more than twice the global rate. Coastal and island nations like Bangladesh, Madagascar and the Marshall Islands face near or total destruction.

But the world’s richest nations have been slow to endorse and support the necessary research, development and governance for negative emissions technologies.

Bad track record with coal

What explains the objections from climate justice advocates?

The U.S. has heavily funded experiments with carbon capture and storage to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from new coal-fired power plants since George W. Bush’s presidency.

Those efforts have not paid off, partly because of economics. Natural gas and renewable energy have become cheaper and more popular than coal for generating electricity.

Only a handful of coal-fired power plants are under construction in the U.S., where closures are routine. The industry is in trouble everywhere, with few exceptions.

In addition, carbon capture with coal has a bad track record. The biggest U.S. experiment is the US$7.5 billion Kemper power plant in Mississippi. It ended in failure in 2017 when state power authorities ordered the plant operator to give up on this technology and rely on natural gas instead.

Other uses

Carbon capture and storage, however, isn’t just for fossil-fuel-burning power plants. It can work with industrial carbon dioxide sources, such as steel, cement and chemical plants and incinerators.

Then, one of two things can happen. The carbon can be turned into new products, such as fuels, cement, soft drinks or even shoes.

Carbon can also be stored permanently if it is injected underground, where geologists believe it can stay put for centuries.

Until now, a common use for captured carbon is extracting oil out of old wells. Burning that petroleum, however, can make climate change worse.

U.S. Energy Department’s National Energy Technology Laboratory

Going carbon negative

This technology may potentially also remove more carbon than gets emitted – as long as it’s designed right.

One example is what’s called bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, where farm residues or crops like trees or grasses are grown to be burned to generate electricity. Carbon is separated out and stored at the power plants where this happens.

If the supply chain is sustainable, with cultivation, harvesting and transport done in low-carbon or carbon-neutral ways, this process can produce what scientists call negative emissions, with more carbon removed than released. Another possibility involves directly capturing carbon from the air.

Scientists point out that bioenergy with carbon capture and storage could require vast amounts of land for growing biofuels to burn. And climate advocates are concerned that both approaches could pave the way for oil, gas and coal companies and big industries to simply continue with business as usual instead of phasing out fossil fuels.

MCC, CC BY-SA

Natural solutions

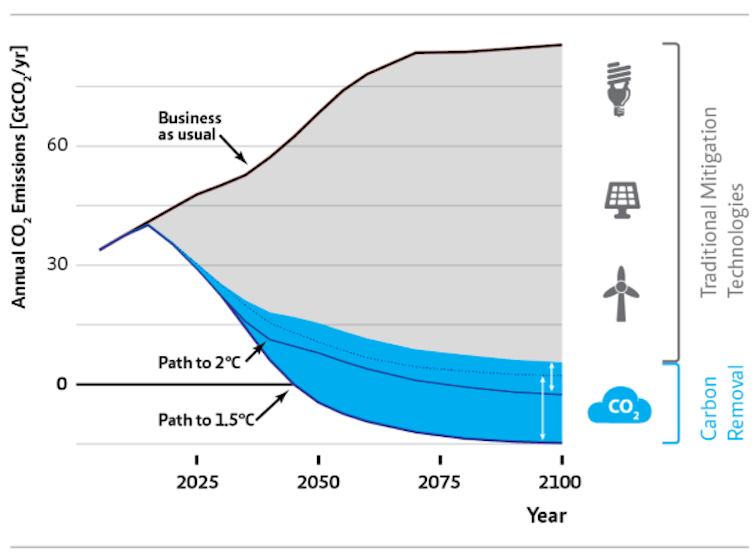

Every pathway to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius in the most recent U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report projected the use of carbon removal approaches.

Planting more trees, composting and farming in ways that store carbon in soils and protecting wetlands can also reduce atmospheric carbon. We believe the natural solutions many environmentalists might prefer are crucial. But soaking up excess carbon through afforestation on a massive scale could encroach on farmland.

To be sure, not all environmentalists are writing off carbon capture and storage.

The Sierra Club, Environmental Defense Fund and Natural Resources Defense Council, along with many other big green organizations, did not sign the letter, which objected not just to carbon capture and storage but also to nuclear power, emissions trading and converting trash into energy through incineration.

Rather than leave carbon removal technologies out of the Green New Deal, we suggest that more environmentalists consider their potential for removing carbon that has already been emitted. We believe these approaches could potentially create jobs, foster economic development and reduce inequality on a global scale – as long as they are meaningfully accountable to people in the world’s poorest nations.

Authors: Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Georgetown University and Holly Jean Buck, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of California, Los Angeles

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.