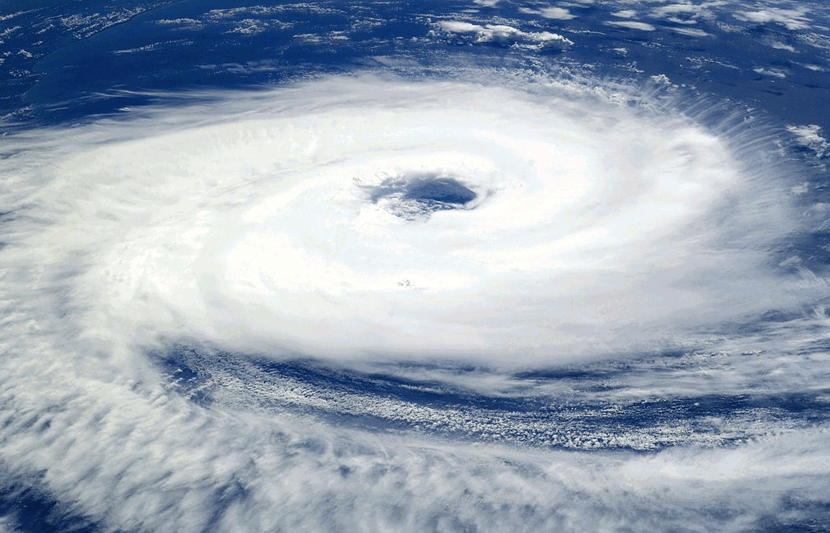

Some of the most destructive, devastating hurricanes in recent years were intensified by climate change, researchers from the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory find.

Their supercomputer simulations proved that climate change increased the amount of rainfall in hurricanes Katrina, Irma and Maria by 5-10 percent.

And the future looks bleak. If humans don’t slow down fossil fuel emissions, increased warming could cause hurricane rainfall to rise by 15-35 percent and boost hurricane wind speeds by up to 29 miles per hour.

“We’re already starting to see anthropogenic factors influencing tropical cyclone rainfall,” Christina Patricola, a scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Earth and Environmental Sciences Area and lead author of the study, said in a statement.

“And our simulations strongly indicate that as time goes on we can expect to see even greater increases in rainfall,” she continued.

Four of the five costliest hurricanes in U.S. history occurred in the past six years.

This research should serve as a wakeup call. If humans fail to switch to renewable energy, hurricanes will only become more destructive, deadly and expensive.

The study

The researchers ran high-resolution climate simulations of 15 tropical cyclones — or hurricanes, the term used in the Atlantic — that have occurred around the world in the past 10 years. They tested how the storms would react to different air and ocean temperatures, humidity and greenhouse gas concentrations.

The simulations used in this study are more trustworthy than past, observation-based techniques used to test the impact of climate change on hurricanes.

“It is difficult to unravel how climate change may be influencing tropical cyclones using observations alone because records before the satellite-era are incomplete and natural variability in tropical cyclones is large,” Patricola said in a statement.

The study was split into two parts.

In the first, the researchers used the simulations to compare and contrast the same storm under different circumstances.

For example, the researchers modeled Hurricane Katrina in a pre-industrial climate and compared it to a model of the storm under current climate conditions. This way, they could determine how much of an impact climate change has had.

“You can certainly use your expert judgment in a better way after the fact,” Michael Wehner, an extreme weather expert in Berkeley Lab’s Computational Research Division and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

“So you simulate the event in the world that was, followed by simulating a counterfactual storm in a world that might’ve been had humans not modified the climate system,” he continued.

In the second part of the study, the researchers simulated hurricanes in three future scenarios of warming.

Average surface temperature has currently risen 1 degree Celsius since the pre-industrial era.

The third, most extreme, scenario simulates a world where warming has increased by 3-4 degrees Celsius.

The researchers found a strong correlation between increased temperature and more intense rainfall and wind speeds.

Although the study suggests a future of increased wind speeds, the hurricanes that were modeled in this study did not indicate any higher wind speed from current warming.

Additionally, the study was not designed to test whether hurricanes will become more frequent or move in different ways.