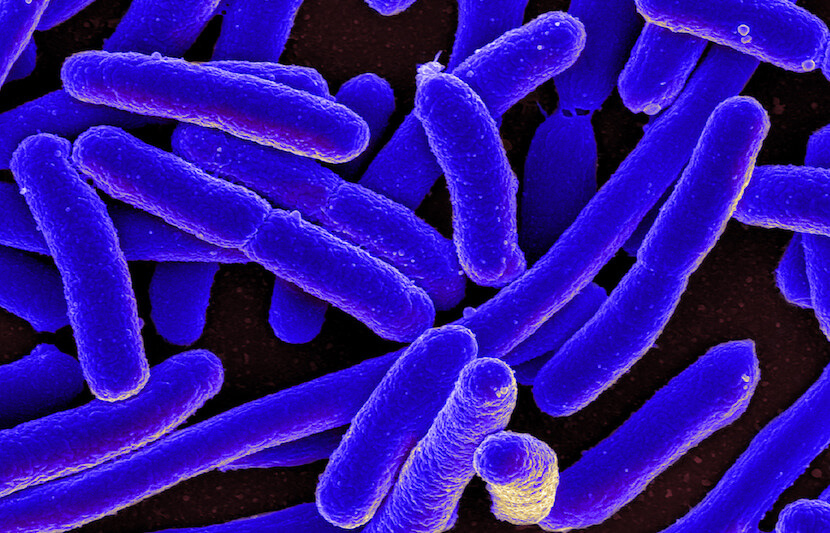

E. coli bacteria could hold the key to the efficient capture and storage or recycling of carbon dioxide, according to a team of researchers from the University of Dundee, UK.

The team’s process uses E. coli to convert C02 into liquid formic acid, which is easier to store and can be used for industrial purposes.

The paper is published in the journal Current Biology.

The study is led by Frank Sargent, professor of bacterial physiology at the university’s School of Life Sciences.

The team has developed a process that enables E. coli to function as a very efficient device to capture C02, which is a major contributor of global warming.

“Reducing carbon dioxide emissions will require a basket of different solutions and nature offers some exciting options,” Sargent said in a statement. “Microscopic, single-celled bacteria are used to living in extreme environments and often perform chemical reactions that plants and animals cannot do.”

E. coli plays a crucial role, as it can grow in the complete absence of oxygen. When it grows, it produces “FHL,” a special metal-containing enzyme that can convert C02 into liquid formic acid. When the researchers placed the E. coli bacteria containing the FHL enzyme under a pressurized mixture of carbon dioxide and hydrogen gas, they found that 100 percent of C02 was converted into liquid formic acid. This happened over a few hours and at ambient temperatures.

“In our very small-scale lab experiment we captured about 11 grams of carbon over 10-12 hours or so,” said Sargent. “This could potentially be scaled-up to increase the yield, and possibly the process could be further engineered to allow continuous recovery of the formic acid product.”

While storing large amounts of liquid formic acid may be challenging, Sargent believes it would be easier to transport, measure and control than CO2. Moreover, formic acid can be used for other purposes.

“Once transformed into the formic acid, this can be used in fuel cells to generate electricity; converted into other useful chemicals by chemists; fed back into other bioprocesses; or simply sold as a commodity (formate is a handy de-icer in wintery conditions!),” he said.

In his opinion, this biologic process could be an important breakthrough in biotechnology.

The researchers hope that the system they devised could be developed and used as a “microbial cell factory” to help capture CO2 from various industries.

“Not all bacteria are bad,” Sargent said in a statement. “Some might even save the planet.”

With millions of tons of C02 being pumped into the air, biologic processes and scientists have key roles to play in saving the planet.

“The burning of fossil fuels by humans is changing our special planet– and not for the better,” he said. “It is therefore up to scientists to come up with intelligent ideas to provide sustainable energy sources and tackle the most pressing issues. Biologists can make a contribution here by understanding, harnessing and adapting natural processes – such as the rapid CO2 capture systems used by bacteria – and collaborating with engineers and chemists to find new ways to negate industrial wastes and maximise our resources.”