Transitioning to a healthier diet isn’t just advantageous to your body — it can also reduce water consumption and promote global sustainability, a new study suggests.

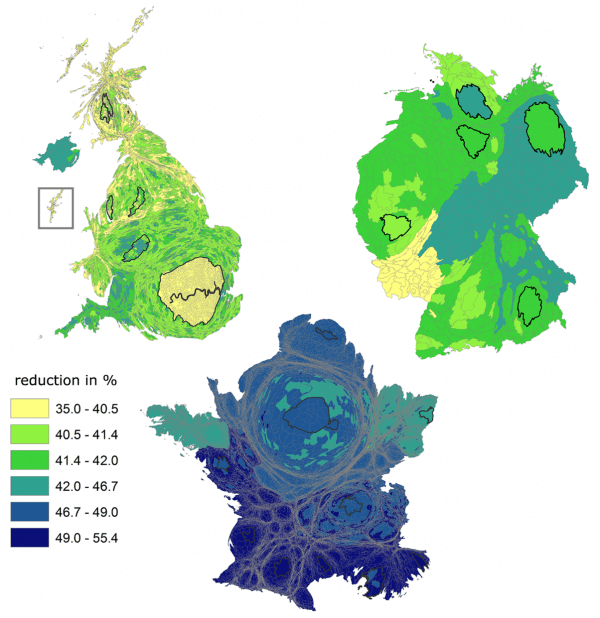

In the study, researchers from the European Commission Joint Research Center (JRC) compared healthy diet patterns to current food consumption practices in 43,000 areas in France, the UK and Germany, and found that eating more healthily could significantly reduce the amount of water required for food production.

The study takes into account socioeconomic factors of food consumption, and is the most detailed nationwide food consumption related water footprint ever documented.

The research comes at a time when water is an increasingly scarce resource, and transitioning to more sustainable food systems is necessary for the health of both people and the planet.

The research is published in Nature Sustainability.

What is water footprint?

Water footprint accounts for the amount of water consumed along the supply chain, and data shows that food requires a lot of water for production, explained Davy Vanham, a researcher on water management at the JRC.

“As an example, the water footprint of beef consumed in the EU amounts to about 9,500 litres/kg. Especially the feed is responsible for this high amount. The actual water cows drink only represent about 1% of the total water footprint amount,” said Vanham.

“This shows consumers that the water required to produce all products and services they consume is much higher than domestic water use at home. Consumers in Western countries can reduce their water footprint substantially by looking at their diets and the food they waste.”

To assess water footprint, the researchers used national dietary surveys to understand the differences in food product group consumptions between regions and socioeconomic status.

The analysis

In analyzing the dietary surveys, the researchers took into account national dietary guidelines, in which specific recommendations for every food product group were given based on age and gender.

They also took into account total daily energy and protein requirements, as well as maximum daily fat amounts.

In addition, they considered socioeconomic data and international food consumption and water footprint databases.

“As food consumption behavior is dependent on socioeconomic factors such as age, gender and highest level of education, we wanted to include this fact in our analyses,” said Vanham.

The findings

The researchers found interesting correlations between age, gender and educational level in regard to water footprint levels.

“We saw that according to the socioeconomic population distribution in the geographical entity we analyzed, the average product group water footprint and resulting total water footprint of such an entity differs,” said Vanham.

“The smaller the population, the more the total water footprint can differ from the national average water footprint.”

For example, in the 35 thousand municipalities in France, the water footprint of milk shows a correlation with the average age of population. This is, because younger people tend to drink more milk than older people, Vanham said.

Similarly, across London, the researchers found a strong connection between the water footprint of wine consumption and the percentage of the population of each area with a high education level.

But perhaps most shockingly, the researchers found that across all geographical entities, the amount of water required to produce our food could be reduced by 11 to 35 percent for healthy diets containing meat, 33 to 55 percent for healthy pescatarian diets, and 35 to 55 percent for healthy vegetarian diets.

Image: ©EU 2018

Overall, the researchers found that animal products — especially meat — have a high water footprint, and that a healthy diet would contain more vegetables and fruit, and less less sugar, crop oils, meat and animal fats.

The importance of reducing water footprint

Water scarcity is happening at unprecedented rates. By 2050, the United Nations predicts, 1.8 billion people will live in areas with absolute water scarcity, and two-thirds of the world could be under water-stressed conditions.

“Already today, many regions of the world face water stress,” said Vanham.

“There is a lot of competition for water resources, for domestic purposes, agriculture, energy and many others. Water is a scarce resource, and the water footprint shows that, due to long supply chains and global trade, a product we consume at home can be produced anywhere in the world under conditions of water stress.”

For these reasons, the researchers at JRC stress the importance of understanding how water footprint relates to current food consumption.

Moving forward, they hope the methodology for the study will be used for other footprints related to food consumption, and that their data will be used by governments to initiate better food-consumption policies.

“The article provides strong communication material to the general public and policy makers, on the most detailed geographical level ever made,” said Vanham.