A common question I have encountered as a teacher involves ways to support students struggling with the writing process. One of the more difficult parts of the writing process is formulation or getting ideas started and flowing.

Graphic organizers are just some of the support methods available to help writers formulate their ideas. Especially when students are still learning to organize their thinking and to keep track of their ideas, research shows graphic organizers can provide students with a road map not only to formulate clearer ideas (written in short phrases to serve as reminders to the writer) but also to improve the structure of their writing.

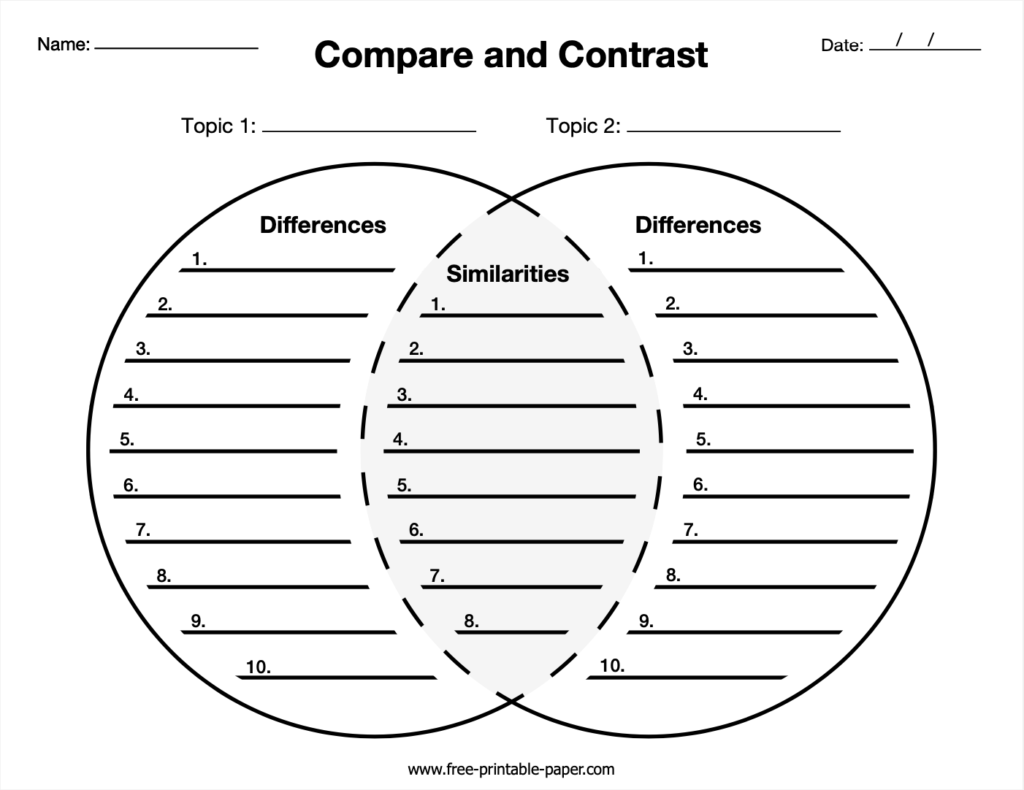

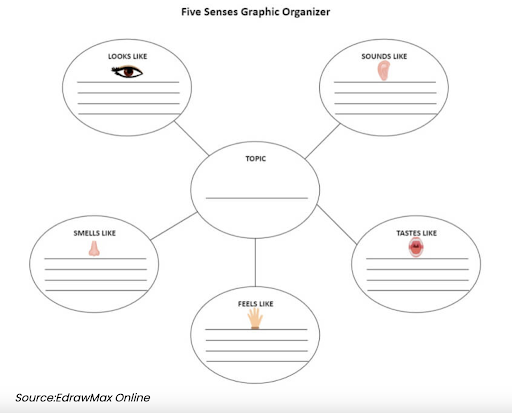

In essence, the graphic organizers break down the overall elements of the writing process and allow the student to tackle the various sections a step at a time. Thus, the magic of the graphic organizer allows the task of the overall writing process to become more accessible and, therefore, more achievable. Examples of common graphic organizers early in a writer’s learning process are below:

While having access to various graphic organizers can surely be supportive for writers, the key is to teach students which organizers to use in different situations and how to recognize those situations. It is also important to simplify the types to use so as to not confuse students with too many various options. The last strategy is a particularly critical component to obtain a successful outcome in the writing process, particularly for English Language Learners or students with language-based learning differences.

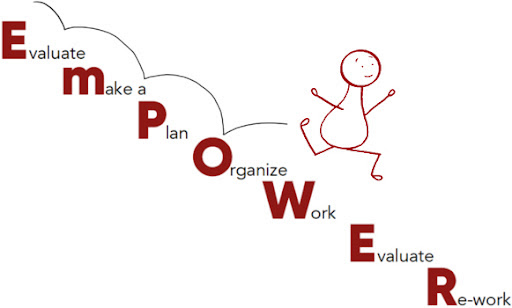

A good resource for teachers looking for guidance about the use of graphic organizers is the training offered on Brain Frames and EmPOWER. Brain Frames make the invisible structures of language visible through the use of a set of visual tools that organize language according to the six fundamental patterns used consistently in and out of school, in writing, and in spoken language. EmPOWER is a companion approach for teaching academic writing that explicitly teaches the writing process with visuals to support the various writing steps.

Not only can students benefit from receiving tips on their writing approach, but educators can also learn more optimal ways to engage students, even at differing stages of ability, based on how they present their writing prompts. For example, many people recognize the traditional writing prompt assigned to students, such as “What is your ideal summer day?” While there is nothing outwardly incorrect with this writing prompt, there are perhaps improved ways to encourage students in their writing process while also increasing overall student engagement.

This can be achieved through variety and choices for the writing prompts. For example, if the prompt revolves around an ideal summer day, a teacher could also offer students a variety of options as to how to approach the prompt thus encouraging students while stimulating ideas to respond to the prompt. This could look like offering different facets of the concept of “an ideal summer day.” This allows students to choose from the choices the teachers provide, which in turn helps to inspire their own writing.

These same strategies can be applied to middle and high school classrooms, which will differ only in the depth and complexity of the writing prompts. In both cases, ideally, an educator’s writing prompt will be accompanied by various options and ways to respond, enough for students to make their choices, which in turn incentivizes them with a sense of agency in their writing experience.

In some cases, students will require additional support from story starters instead of prompts, to develop grade-level writing skills. A story starter is where the beginning sentences or paragraph of the prose is provided, which helps get the student’s writing flow going and then it is the job of the student to continue the flow of thought.

Even further scaffolding can be offered, which includes the method of breaking down the process of writing formulation to the sentence level, leaving it to the student to complete the sentence provided – a sentence starter that could be as basic or as complex as the student’s intellectual abilities require.

Word banks of vocabulary associated with the topic can bridge formulation frustration, helping students with language-based learning differences and English Language Learners.

Additionally, opportunities to brainstorm verbally based on the prompts through sharing stories with a partner before sitting down to start the writing process would “get the juices flowing” and increase academic discourse and supportive community within the classroom.

There are many strategies available to guide students through the process of writing formulation, but the real trick is understanding the why behind the difficulty with formulation. Sometimes, students have too many ideas and feel overwhelmed or struggle to narrow down the choices effectively. Others still will just get blocked as soon as they are asked to write, much like the challenge of confrontational naming when having to retrieve a specific vocabulary word from the brain – the sudden demand on the mental systems causes a lockdown. Sometimes, students just need structure to get started. Observing your students, talking with them about their experiences, modeling the language associated with the writing process, and supporting regular student reflection about their learning will all help in the process of both the student and the teacher understanding the why behind their struggle and help give them direction towards success.

In the case of many Gifted and Twice Exceptional students, their asynchronous development – which is characterized by large peaks and valleys in different areas of development – can also strongly factor into their growth as a writer. For example, young children who have only been on the planet for a certain number of years have had a limited period of time to develop the muscle and fine motor skills to produce the output needed when writing. Asynchronously developing students tend to have novels in their brains, essays in their speech, and just words or sentences in their written output. The frustration at how slow their hand is at getting ideas to paper can cause them to be minimalistic, rushed, and/or sloppy in their application of these skills.

If this is the strong why behind your student’s challenges, then it is important to not only use a variety of strategies as described earlier but also give them opportunities to use adaptive technology like speech-to-text or a scribe, so the fullness of their ideas is honored and heard. Mixing in opportunities for students to dictate their writing increases self-efficacy and engagement in an area that they may perceive as a weakness due to their asynchronous development. No matter where the challenge is, the key is to determine where the struggle is coming from so you can thoughtfully prescribe methods to support it.

Karen Blumstein is an educator with a background in elementary and special needs education. Trained in Orton-Gillingham Approach, she has nine years of experience working as a self-contained fourth grade classroom teacher and as a tutor at a specialized school for the dyslexic. Recently, Karen earned a certification in Gifted and Talented Education from the University of Connecticut. She has experience understanding gifted education from both the perspectives of an educator and as the parent of a gifted child. Karen is passionate about gifted education and supporting goals that will produce enjoyment, engagement, and enthusiasm for learning.