The night is pitch-dark and silent. Five boys fit into two twin-sized beds, hardly able to move, but still a rare luxury in the neighborhood. Crawling over his cousins to get down from bed, a boy tiptoes to his mother’s room and spends the night on a mat, but with more space to himself.

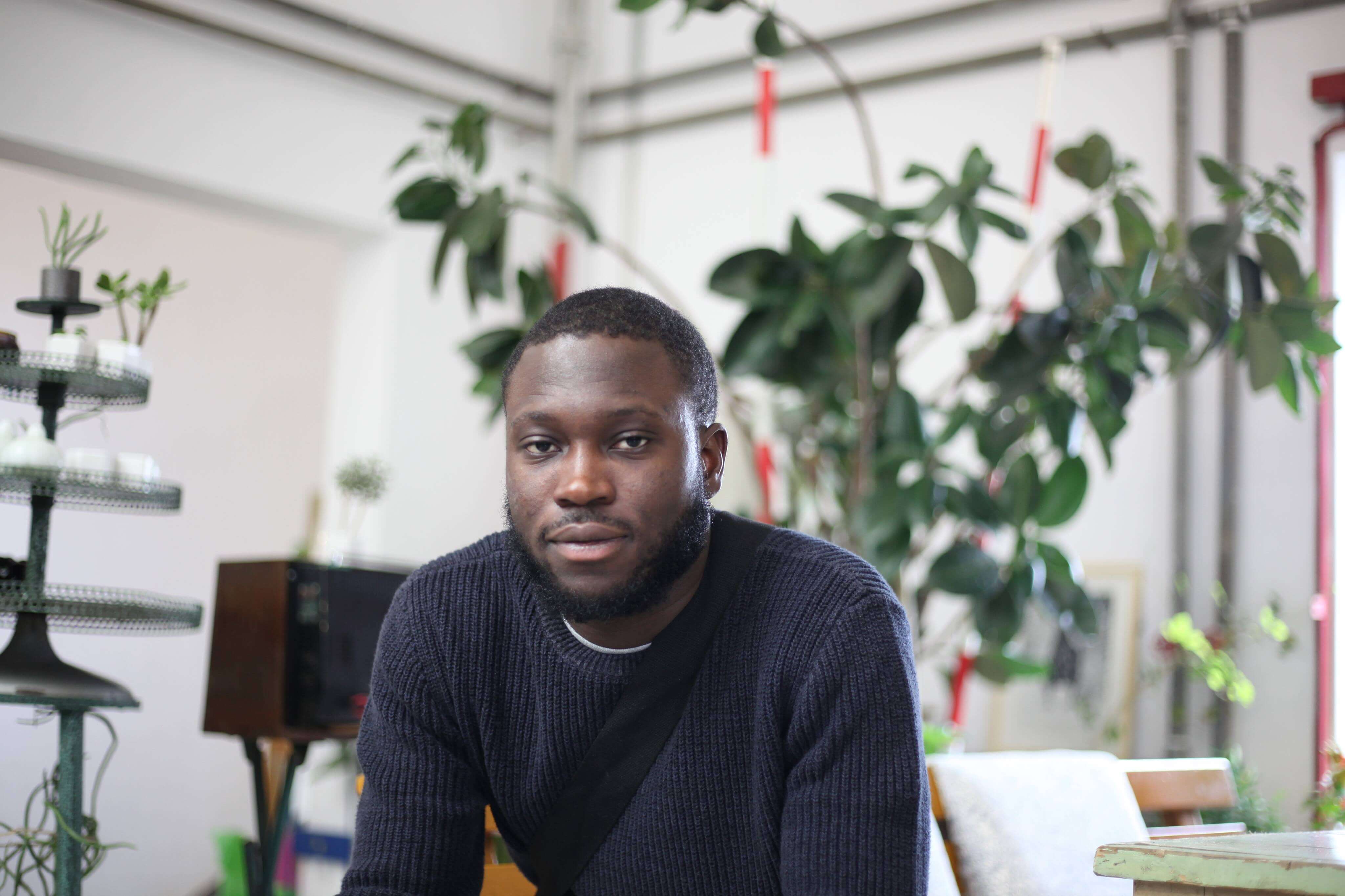

Growing up in Guinea, Aboubacar Komara, 25, found home to be the best place on earth, surrounded with loving families, but always crowded.

“I remember growing up, we had over 20 people in our home. So we have cousins, relatives from the village that were living with us,” he said.

Now, Komara, who graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in architecture from UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design in May this year, is using his architectural background and his award money of $25,000 to build affordable housing for his community.

As overpopulation left much of Guinea’s urban residents in slums, where they struggle with lack of housing and proper sanitation, Komara is using his concept of Kaloum Bankhi, a low-cost, sustainably built housing, to build a community of hope for the city’s most vulnerable population.

Meaning home of Kaloum, a prototype of Kaloum Bankhi is located in the slums of Kaloum, a city center of Conakry, the capital of Guinea.

Life in Guinea

While his life in Guinea wasn’t perfect, Komara was always reminded to be grateful.

Although he had to share two twin-size beds with four other cousins and a bathroom with many relatives, he never had to alternate sleeping hours like many of his neighbors did.

His parents made sure he didn’t go sleep hungry. They encouraged him to work hard in school, but also to enjoy life and laughter.

He specially loved following his dad, who was a civil engineer, to work and watch him draw and build.

“Because of him, I developed a certain love for architecture,” he said.

But, when Komara went to the university to major in architecture, which he took upon to honor his dad’s passing in 2008, he quickly realized opportunities were few.

“Not having like a rich parent to help me travel, I didn’t really have much hope to get out of the system,” he said.

One day, when he saw his best friends applying for a diversity visa lottery, a highly competitive visa to the U.S. that accepts less than 1 percent of Guinean applicants per year, he was initially reluctant but then thought “Why not?” to himself.

In May 2013, Komara found out he was the only one lucky enough to obtain a visa to the U.S.

Six months later, in November, he arrived in the U.S. and lived with his aunt — a teacher in Palmdale, California — where he could focus on continuing his education at a community college in Los Angeles without worrying about money.

“My goal is to give back. I feel like I got the baggage of the entire group, you know,” he said.

Doing his part

Even when he transferred to UC Berkeley in 2016, Komara always had Guinea in the back of his mind.

In the fall of 2017, during his senior year, he worked on a project to design a one-room dwelling for any site of his choice. He immediately chose the slums of Conakry, addressing problems like lack of housing and sanitary conditions.

While researching, he was inspired by a shotgun home, a popular housing type in southern U.S. that originated from West Africa. In its journey, Komara saw himself as well.

“It’s all about migration. A project that once was part of West Africa, but has migrated and it’s used in the U.S., and then now I have to migrate that back,” he said.

After realizing how feasible his design came out to be, he told the class that he wanted to build it in Guinea the following summer. No one believed him.

“I myself didn’t really know how this was going to happen, but I just had put it out there,” he said.

But he believed in it. And somehow, things did play out for him.

Some time later, Komara found out that reward money he received from a poster competition he previously won messed with his financial aid. While waiting in the financial aid office to fix the problem, he saw a flyer about the Judith Lee Stronach Baccalaureate Prize, which supports recent graduates in advancing the projects they began during their undergraduate studies.

“I was like, ‘Are you kidding me? This is what I’ve been looking for,” he said.

He worked hard to pull together a final proposal. In April, he was awarded $25,000, which he used for his sustainable housing project.

In the field

A few weeks after graduating in May 2018, Komara returned to Conakry to build a prototype of Kaloum Bankhi with a group of faculty and architecture students from the Institut Supérieur d’Architecture et D’Urbanisme (ISAU).

He had two goals: space consciousness and sustainability.

According to the United Nations, Africa as a whole will see its population double by 2050. Cities will become overpopulated and, starting with the poor, more people will suffer from lack of housing and proper sanitation.

To address this, Kaloum Bankhi is space conscious, meaning no space is wasted.

In Kaloum Bankhi, as small as 10 by 25 foot, there are three rooms that opens with a normal swinging door, one leading to an adjacent one.

During daytime, the entire space can be opened up for maximum space. During night time, doors are closed and Murphy beds and multi-purpose furniture that can be transformed into couches and beds are pulled down for an entire family to sleep together.

“This is thinking about the future of Africa, or future of Guinea to be more specific, or Conakry, where these homes will accommodate a lot of people all at once,” Komara said.

Second, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, in 2017, nearly 40 percent of energy consumption in the U.S. was from buildings.

“Climate change is not only a problem of the U.S. It’s a global problem. I wanted to make sure Guinea is not left out in the fight against climate change,” said Komara.

Kaloum Bankhi uses sustainable and locally sourced materials. This is not only healthy for the environment, but also a reminder to the people that they don’t have to use materials unnatural to Guinea just to copy Western architecture.

All locally sourced right from Guinea, Kaloum Bankhi’s bright green corrugated metal walls and traditional West African fabrics, beaming with vibrant colors, are in stark contrast to its neighboring houses with cement and metal walls torn apart by time.

“The problem that we face in Guinea is that there is no true architecture that’s from Guinea. Instead of copying from others, we should try to learn from our environments and create something that’s unique to us,” Komara said.

Most importantly, Kaloum Bankhi is affordable and doesn’t take long to build.

Although even the local contractors and the students doubted the idea at first, Komara’s team successfully built the prototype for less than $6,000 in two weeks of the most rainiest season in Guinea.

“The most rewarding thing was seeing people in the house,” he said. “People from my community is coming to me and saying ‘Oh, I’ve never seen anything like this. I think it’s a really cool idea.’ I think that was refreshing.”

Although no one currently lives in the house because of tour and study purposes, it will soon be open for a family in the next 5-6 months.

Learning by doing

While many architecture schools are moving in this direction, Komara believes more students should be exposed to field work, where they can apply what they learned in class.

He advises students currently in school with great ideas to speak out because you never know when you will meet someone with the power to make it possible.

Currently, Komara is back in Guinea and working on building more prototypes. He will co-teach a design build studio at the ISAU, where he hopes to build design competitions and exchange programs with U.S. and European schools.

He also plans to design a middle school that will specifically incorporate design classes within its curriculum.

“Your learning is not complete unless you teach someone else what you learned. Because if you don’t teach anyone else, once you die, it’s just gone,” he said.

“Each one teaches one,” as Komara often tells himself.