Mental health — specifically anxiety, depression and stress — is a pressing issue on college campuses. Every year, more than 150,000 students from over 400 colleges and universities in the U.S. and internationally seek mental health treatment, according to the Center for Collegiate Mental Health at Penn State University.

But now, researchers from the university suggest that there is something individual people could try to reduce their unpleasant feelings.

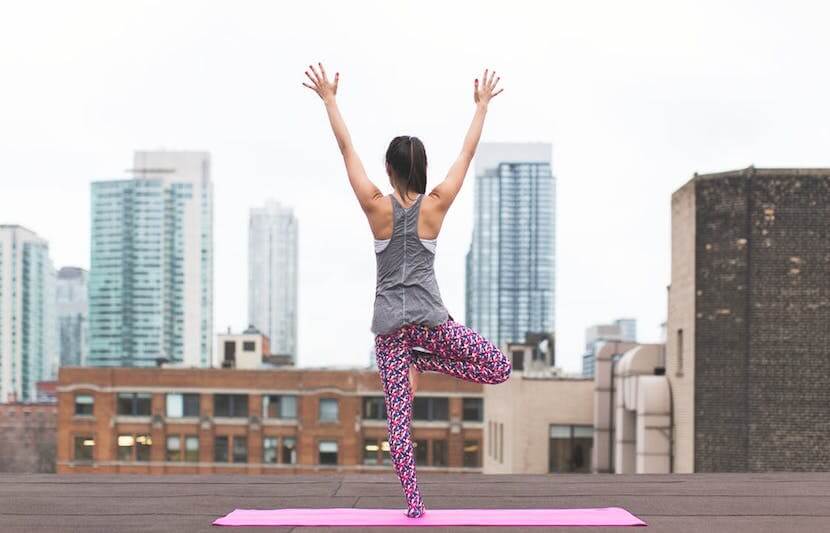

The solution may be “moving mindfully” in everyday life.

In the study, the researchers found that students reported being less stressed when they were being more active and mindful than they typically would be.

“People may be able to reduce their unpleasant feelings by moving mindfully without changing their everyday behavior,” said Chih-Hsiang (Jason) Yang, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Southern California, who led the study while earning his doctorate at Penn State.

What does “mindful” mean?

Being “mindful” has multiple definitions in literature. Some researchers emphasize moment-to-moment awareness and others focus on self-acceptance and compassion to oneself and others, explained Yang.

One of the common definitions is “to elevate one’s awareness and attention to every present moment experience and embrace a non-judgmental attitude towards any physical or mental experience encountered,” said Yang.

Perhaps the most critical concept is to pay attention to the present. The researchers emphasize that people shouldn’t dwell on the past or think too far into the future.

“An easy way to start with practicing mindfulness is directing one’s attention to some ‘always accessible targets,’ such as our breath and steps,” said Yang.

“For example, sitting in meditation that focuses on the rhythm of breathing is commonly applied to various mindfulness programs. However, as physical activity researchers, we would love to see mindfulness being practiced in a relatively active way rather than in a sedentary posture.”

At times, it can be difficult to ask people who are struggling with their mental health to run or go to the gym to receive the psychological benefits of being active.

This study suggests that people perhaps do not have to change their daily habits. Instead, they just need to alter their state-of-mind when moving around.

“If someone is looking for a way to manage these kinds of negative feelings, it may be worth trying some sort of mindful movement,” said David Conroy, professor of kinesiology at Penn State and co-investigator of the study.

“This option may be especially beneficial for people who don’t enjoy exercise and would prefer a less intense form of physical activity.”

The study

The researchers gathered 158 Penn State students to participate in the study.

Each student was required to download a special app called Paco, which asked them several questions about their momentary activity and mental experience every day for two weeks.

The questions were randomly delivered to the students throughout the hours they were likely awake.

Each time Paco let out a signal, it asked the students where they were, what they were doing, if they were feeling stressed or anxious, and included questions to assess their mindfulness.

“Based on the results from our statistical analyses, we observed a synergistic effect when students are more mindful and more active in a given moment then their usual level,” said Yang. “The combination of moving and being mindful was associated with less unpleasant feeling states than either moving or being mindful by itself.”

The researchers noticed that previous mindfulness studies compared students, rather than focusing on fluctuations of mindfulness in the same student.

“Most studies in this area have focused on the differences between people who are more versus people who are less mindful, but we saw that college students often slipped in and out of

mindful states during the day,” Conroy said in a statement. “Developing the ability to shift into these states of mindfulness as needed may be valuable for improving self-regulation and well-being.”

What’s next?

“The next step is to conduct randomized controlled trials – our gold-standard method for testing causal relations – to determine whether mindful walking improves affective experiences,” said Conroy.

Preparation for those trials has already begun.

After the study, the researchers completed an outdoor mindful walking intervention program for older adults.

For one month, they practiced different mindfulness techniques as they walked slowly.

“Participants in this study also reported lower feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression after their mindful walking sessions,” said Conroy. “Most importantly, they seemed to really like the program and most were still practicing mindful walking a month after the program ended in the dead of winter!”

Additionally, literature has suggested that practicing mindfulness may improve working memory and self-regulation.

“It would also be interesting to study whether being more mindful in our everyday life could help people to sustain their physical activity motivation or ‘remember’ their goals for being active,” said Yang.

“We are thus aiming to understand whether practicing mindfulness may emerge as an intervention strategy to promote physical activity and health in different populations.”