In early March, colleges and universities across the United States shut down their campuses and transitioned to online classes. Although they were acting to slow down the spread of COVID-19, the closures have negatively impacted hundreds of thousands of students, leaving many jobless, homeless or struggling to access the internet.

Students depend on their campuses being open and running. Many rely on the dormitories for housing and their meal plans for food. They work for their schools or for local businesses. When those avenues closed, many lost their ability to pay rent or bills or even afford their groceries.

Unfortunately, the $2 trillion stimulus package passed recently to provide some financial relief to Americans excludes the majority of college students. To qualify for aid under the CARES Act, they need to be deemed as independent but many students are still listed as dependents by their parents. And their parents won’t receive any money for them either, as the stimulus package doesn’t award money for dependents over the age of 17.

Despite their struggles, “no one is really talking about college students right now,” said Carter Oselett, a student at Michigan State University.

Oselett personally considers himself to be one of the lucky ones. Unlike many of his peers, he has a safe home to go back to and was able to keep his job. But he’s far from being worry-free.

Oselett is currently living with his parents so that he can help his mother cook and deliver meals to his aunt, who was recently diagnosed with COVID-19. His aunt’s husband is overcoming tonsil cancer, so his cousins are left to do much of the housework while also managing their online schooling.

Most of his friends at school were laid off, he said, since nearly everyone of them worked for the university or at a local bar, bookstore or restaurant. And others were forced to go back to toxic households.

“I have a friend whose family isn’t comfortable with her gender identity and how she identifies, and she has to go live with that,” said Oselett. “She’s lucky that she has a family to go back to, but college is a time to discover yourself … and it’s really unfortunate that some students have to cut the year short to go back into a household that might not respect them.”

Oselett works as a deputy state director for Rise, a nonprofit organization dedicated to making higher education accessible for all. Temporarily, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Rise has shifted some of its focus towards helping the students most affected by campus closures.

“Early on in the virus, we were hearing from students on our team and in our network that they were being laid off from jobs, that they were having their campuses shut down, and in some cases they were being evicted from their housing,” explained Maxwell Lubin, the CEO of Rise.

“We saw pretty quickly that there was overwhelming need,” he added. “College students, by nature of typically being part-time employees and being campus-dependent for their jobs, are particularly economically vulnerable.”

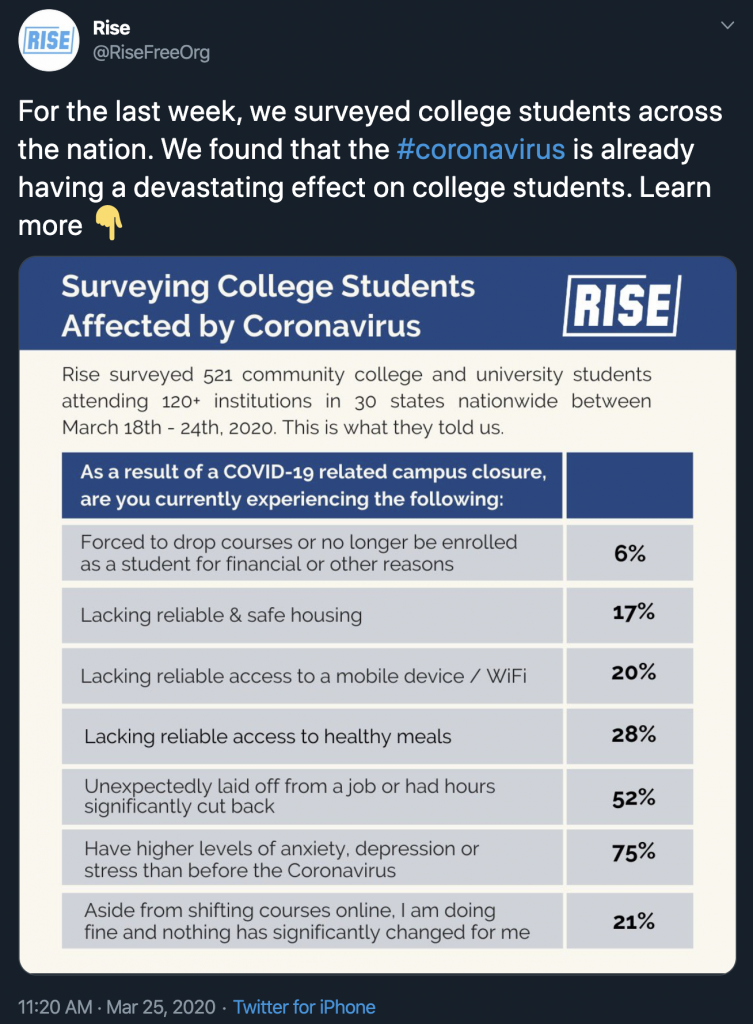

In the middle of March, Rise conducted a survey that gathered responses from 500 students from more than 120 colleges nationwide and found that 52 percent of them had been laid off or had their hours significantly cut back.

Since that was a few weeks ago, Lubin imagines the numbers would be even higher today.

Currently, Rise is working in collaboration with the nonprofit Believe in Students (BIS) and Edquity. Together, they’ve created a student relief fund and an online portal through which students can seek guidance from experts on how they can access aid like unemployment insurance, food stamps or money through their own college or university’s emergency relief funds.

“They write in and say what they need help with, and we have this big committee of volunteers who are sitting there every day and taking those requests and helping people figure out what they should do to get assistance,” explained Sara Goldrick-Rab, the founder of BIS, a professor of higher education policy & sociology at Temple University and founding director of the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice in Philadelphia.

It’s been less than a month since the nonprofits released their online help portal, and nearly 900 students have already applied for guidance, Lubin said. Each day, about 60 more are applying.

The group’s student relief fund, which Godrick-Rab said has raised about $105,000 to this point, was primarily set up to supplement those run by colleges, universities and government systems so that students who need money immediately can get it in a timely manner.

The relief funds administered by colleges, universities and government systems have the capacity to serve a much greater number of students, but those who apply for those grants often have to fill out extensive applications, and it can take weeks before they receive any money.

Currently, the federal government is working to disburse $7 billion to colleges and universities so that it can be used for emergency grants to college students. Colleges and universities have yet to receive that money, however, and it’s uncertain when they will.

The money from the nonprofits’ student relief fund is being given out through two pre-existing programs. Some of those in the Dallas area are receiving their money through the Edquity App, but the bulk of the money is being delivered through BIS’ FAST Fund program.

The FAST Fund was created in 2016 and this is how it works. Professors at colleges and universities across the country sign up to administer a FAST Fund program at their respective schools. Money from the fund is then disbursed to the professors and they, just like a friend, can give the money out to students who need it. While many professors require students to submit at least some form of application, the point of the program is to remove the red tape.

As the campus closures have resulted in an uptick of students requesting aid, more and more professors have started a FAST Fund at their institutions. And that’s something Goldrick-Rab said she’s really proud of.

Robin DeRosa, who teaches interdisciplinary studies at Plymouth State University, is one of those professors. She started a FAST Fund just a few weeks ago so she could provide aid to Plymouth State students affected by COVID-19.

“When our school closed for remote learning, and the rest of the state started closing things down as well, I realized the biggest challenge my students were facing was not transitioning to online learning, it was actually surviving the upheaval in their lives,” DeRosa explained.

“Lots of my students just immediately overnight lost their jobs, and a huge number of them are living paycheck to paycheck,” she added. “I started hearing stories from students about how desperate they were. And I realized that any funding they were going to get from the government or even support from the school was going to take too long to get to them. And they were going to have big problems before then.”

DeRosa received about $5,000 from the FAST Fund and raised an additional $2,559. Within a day, it was all dispersed among 43 students.

By dividing up the money, typically in sums between $100 and $300, DeRosa said they were able to serve 100 percent of the students that applied.

“The response was absolutely immediate,” she said. “What that also allowed was for the university to then get its more official larger scale fund up and running. But, it’s really hard to leverage big institutional drives like that so quickly. So, we were able to meet that little gap in between getting the university fund off the ground and the pandemic hitting hard.”

To receive a grant, students were required to submit a brief application describing their situation.

“My colleague and I who read them together, you know you couldn’t help but be in tears to hear what they were dealing with,” said DeRosa. “It was crazy.”

Kristin Bivens, an associate professor of English at Harold Washington College in Chicago, also recently started a FAST Fund at her institution.

Bivens said she had an urge to help when she saw the struggles students were going through. But, quarantined in her home, she didn’t know exactly how she could. Having kept up with Goldrick-Rab and the work she does highlighting the financial struggles many college students go through, however, Bivens decided to reach out and apply to administer a FAST Fund at Harold Washington.

There are government grants that college students in Chicago can apply to, but they are also paperwork-heavy and it can take weeks before students receive their money.

Bivens said she was motivated “to get money to students without it being encumbered by all of the layers of bureaucracy.”

While a handful of the FAST Fund grants have gone towards helping Harold Washington students pay their rent, Bivens said the majority of grants are going towards students to help them pay their internet bills so that they can continue their online education.

Michael Rosen, a now retired professor of economics at the Milwaukee Area Technical College (MATC), has been running a FAST Fund for nearly five years. He too said he’s seen an uptick in grant requests amid the COVID-19 pandemic, mostly coming from students who need access to computers.

In years past, Rosen explained, he and his colleagues, who help run the FAST Fund, typically wouldn’t allot grants to students who asked for money towards computers because there’s only so much to divvy out and students could utilize computer labs. But, with those labs closed, students no longer have that option. So, Rosen has been buying computers online and having them shipped directly to students’ houses or apartments.

Throughout his time running the MATC FAST Fund, however, the bulk of money raised has typically gone towards helping students pay their rent.

“The biggest demand for us every year has been around housing,” said Rosen. “It is a really poor community. And most of our students come from Milwaukee County where rents are very high, and students are struggling with it.”

Having run a FAST Fund for so long, Rosen knows just how impactful it can be.

He told the story of once giving a grant to a student who, despite working, had been forced into homelessness due to domestic abuse. A colleague of Rosen’s, who was her professor at the time, noticed her grades slipping, which was peculiar because she had typically been a stellar student. After inquiring about why her test scores dropped, the professor understood the situation. And soon after, the FAST Fund paid for the deposit on her new apartment.

“Her grades went right back up,” said Rosen. “She graduated as an RN in January of the following year, and passed her RN state boards that January. So, within about a seven-month period, she went from homeless to earning $30 an hour as a nurse. We don’t know what would’ve happened to her if we didn’t pay the security deposit.”

Rosen typically has a bit more money to allocate through his fund than most, as he goes above and beyond by running galas and parties to fundraise. The first year he ran the fund, he was able to help 27 students, but that number has since increased. In 2018, grants were awarded to 109 MATC students. Last year, the fund helped 157 students. This year, although it’s just early April, the fund has already granted money to more than 200 students.

If you’re a student who needs help amid the COVID-19 pandemic, seek advice here.

If you’re willing to make a donation to the student relief fund, click here.