A team of student-researchers from the University of Central Florida (UCF) has developed high-tech sponges capable of cleaning up ocean water after oil spills.

The sponges can soak up oil while repelling water, and they don’t leave behind any toxic byproduct. The collected oil could even be recycled for future use.

“Oil-water separation is an emerging global issue that has been found across the globe because of increasing oily wastewater, as well as frequent oil spills,” said Woo Hyoung Lee, assistant professor in the Department of Civil, Environmental and Construction Engineering at UCF and principal investigator and mentor of the project.

The current standard treatments for separating oil from water involve applying chemicals and dispersants or using absorbent mat pads, resulting in potential byproduct pollution, he explained.

“The disadvantages associated with the multitude of oil spill response methods demonstrate a clear motivation for using an innovative material to aid in the overall reduction of contaminants found in our water resources,” he continued. “Our motivation of these high-tech sponges is for effective oil-water separation methods which can be recycled without any production of hazardous byproducts.”

Nationwide Sustainability Competition

The team’s research project won a $15,000 award in phase one of the People Prosperity and the Planet (P3) design competition sponsored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The UCF team was one of just 31 student teams across the country that won the monetary grant, which was awarded to winning teams so they could develop their ideas and showcase their work at the EPA’s National Sustainable Design Expo last month.

“The expo provided a chance for us to showcase our oil removal design to a wide audience of federal agencies, industries, science and engineering advocates, and the general public,” said Lee. “For two days, we had lots of visitors in our demonstration.”

For phase one, the student teams had to develop proofs of concept.

In phase two of the competition, the teams compete for an additional $75,000 grant to help them implement their inventions in real-world conditions.

“In phase two, we will focus on how we can scale-up this technology for the real-water situation and expand the current proposed system into more systematic way, providing relative engineering guidelines, as well as life-cycle assessment,” said Lee.

The project has allowed the students to test their academic and technical skills and taught them to work as a team.

“The project has given our interdisciplinary team of students an excellent experience in how to work together to solve problems putting to use their areas of expertise and learning from each other,” Lee said in a statement. “It’s how the real world works.”

How the Sponges Work

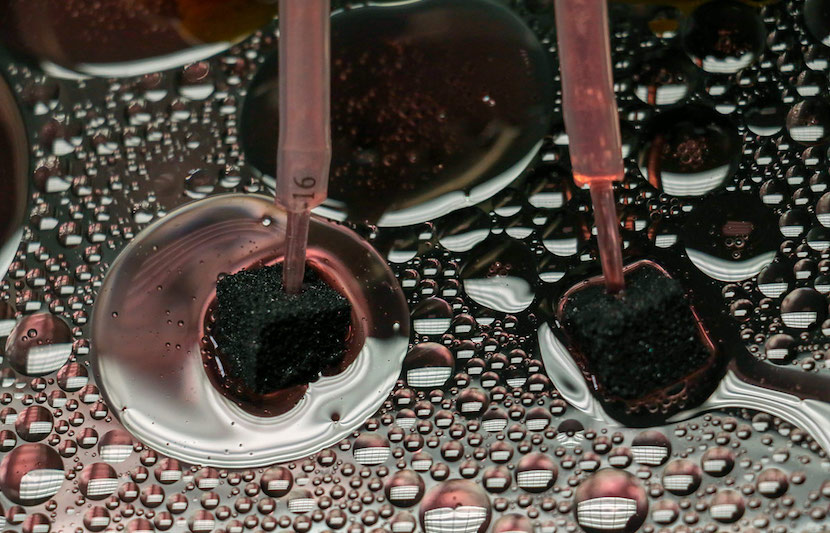

The team developed superhydrophobic MoS2-coated sponges.

“Our system utilizes the dip-dry method to layer MoS2 along the porous substance in order to induce superhydrophobicity and superoleophilicity for the selective separation of water and oil in a sustainable manner,” said Lee.

The researchers have proven that the sponges could separate water and oil, allow for the recovery of the oil, and could continue to perform highly after multiple uses.

Implications

The use of these sponges could eliminate secondary environmental pollutions, which often occur in the cleanup of oil spills.

“The proposed system will represent a field-deployable, easily operational, cost-effective, and highly efficient oil-water separation method that does not require highly trained technicians and/or sophisticated equipment or devices,” said Lee.

The researchers plan to test their device in various conditions, from freshwater to ocean environments. They expect their technology to serve as a tool for fast cleanup actions after unexpected oil spills.

What drove the students?

The diverse group of students was motivated by personal experiences, and they each brought unique skill sets that helped the team develop their invention.

“My role on the team was to bring a biotechnological perspective to the project, which focuses on the cellular and biomolecular process of what we are trying to achieve, and expand on those processes in application to commercial production,” Dianne Mercado, a student pursuing a bachelor’s degree in biotechnology, said in a statement. “While biotechnology is my specialty, one of the best aspects of being part of this project is having other students who come from a variety of fields work together to create something truly interdisciplinary.”

Hernan Sabua, a civil engineering major and team leader, has wanted to invent something to aid environmental protection and public health for a long time. His motivation stemmed from his family background.

“Ever since I was little, I wanted to make a difference in the environmental sustainable aspects of engineering,” Sabua said in a statement. “I had extra motivation in the project because of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010, which occurred near Mexico, where my family is from.”

Additional student members of the team include Conner Thompson from biomedical sciences, Kelsey Rodriguez from environmental engineering, and Dwight Davis from mechanical engineering.

Yeonwoong Jung, assistant professor in UCF’s NanoScience Technology Center, and Jae-Hoon Hwang, a postdoctoral scholar from environmental engineering, serve as the team’s co-principal investigators.