The recent shooting at the Pittsburgh synagogue, which killed 11 people, is a sobering reminder that Americans are not safe.

That instance, along with the Charleston church killings, the riots in Charlottesville and others, have proven that violence towards minority groups is once again becoming a staple of life in the United States.

And many scholars are blaming this on a rise of hate speech.

Nazi and white supremacist rallies have grown in size and strength, allowing members to feed off of each other for reassurance when spewing hateful, racist speech.

Ten years ago, finding a morally confident Nazi wasn’t as easy.

“People had to sort of meet up in somebody’s backyard. They had to be relatively close to have these sorts of Klan gatherings,” said Billie Murray, a rhetorical activist scholar and an associate professor of communication at Villanova University.

“Now it is clicks away on the internet and they have a whole community of people to support them and reinforce these sorts of problematic views,” she continued.

Murray has been attending counter-protests to KKK and Nazi rallies, with a special interest in Antifa protesters, since 2013.

She dives into the middle of the conflicts to observe actions and rhetoric used by both sides. At the front of police lines, she observes how counter protesters work together to fight against white supremacists.

She then brings her experiences back to teach her students at Villanova.

She is currently working on her book, titled “Allied Tactics: Public Responses to Hate Speech.”

Emboldening racism

Murray started the project because she was interested in how communities organized against hate groups. Her studies were sparked by attending counter-protests against the founder of the Westboro Baptist Church, who led anti-gay rallies at military funerals during the war in Iraq.

The U.S. government and Supreme Court have put it on communities to respond to these hateful rallies with more speech, explained Murray. “My interest was ‘what does more speech look like?’,” she continued.

When Murray first started attending the events, they were much smaller on both sides. But through 2013 and then the presidential election cycle, she quickly saw attendance rise and hateful rhetoric become emboldened.

Social media has allowed closeted KKK and Nazi supporters to find a community of like-minded people, making them feel more comfortable and confident in their opinions.

Many Klan, Nazi and white supremacist groups developed the thought that their style of thinking is a “credible difference in opinion that should be a part of our discourse and how we understand things,” Murray said.

“Then they see this on a national stage with the rhetoric coming from the Trump administration,” she continued.

Trump’s remarks after the violent, deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville that “there is blame on both sides,” for example, makes white supremacists feel that their opinion holds equal weight to those protesting against them.

What can be done?

“We have decided as a country that we can’t regulate hate speech, and I disagree with that,” Murray said.

Although freedom of speech is a pillar of the U.S. Constitution, Murray, along with many others, worry that making room for hate speech can lead to violent hate crimes.

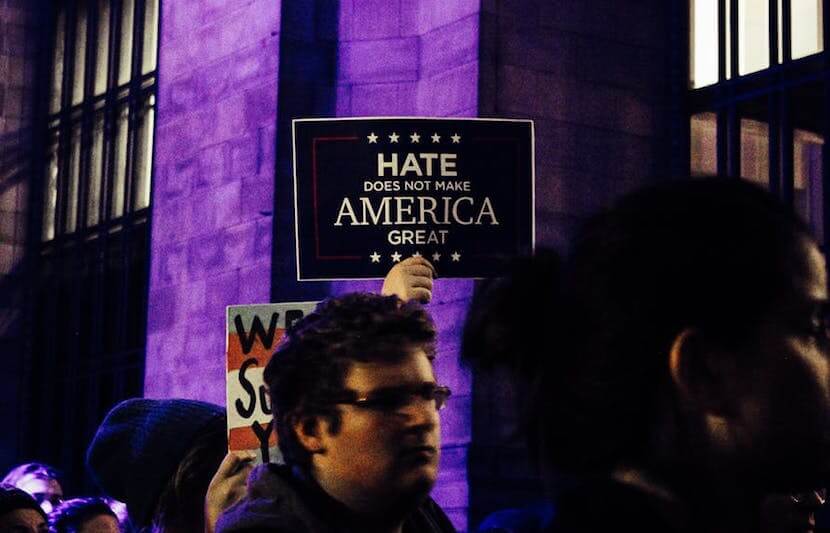

So without the ability to regulate hate speech, citizens have turned to “more speech” as a means to retaliate and weaken the claims of white supremacists.

Many of Murray’s studies have focused on what “more speech” looks like.

She has found that LGBTQ communities have successfully combated hate speech by celebrating their identities and diversity.

Some other counter-protest groups have used combative speech techniques to try to de-platform white supremacists and keep them from furthering their message.

But silencing these groups is not easy, especially because they are protected by the government.

“They are given a platform, and police protection is even provided for them,” said Murray. “I rarely see any type of protection or assistance for those people that are engaging in more speech, particularly in a public space.”

“I see police violence against even peaceful protestors,” she continued. “That is really problematic and detrimental to our democracy.”

Protesters aren’t protected from harassment on social media, either, which can also be damaging.

People who criticize hate speech online can be threatened and harassed, and this can scare people into silence, effectively removing them from the democracy, explained Murray. Failing to create safe spaces for criticism is limiting free speech.

Key lessons

Developing a new generation of broader-thinking, more accepting people might be the best solution to limiting hate speech and violence in the future.

Murray teaches her students about the importance of a well-rounded, rhetorical education to create active and responsible citizens and critical thinkers.

Higher education is “not just about your job, but about the kind of person you’re going to be, the kind of communities you’re going to be involved in, if you’re going to be involved in those communities in a responsible and ethical way,” Murray said.

Developing people who think rhetorically is the most sustainable way to preserve a safe, accepting and effective democracy.