It is not breaking news that the U.S. is polarized. While many factors have played into the separation of American ideas, the finger is often pointed at social media.

But now, new research from the University of Pennsylvania (Penn) proves that social media can effectively reduce polarization on key issues like climate change.

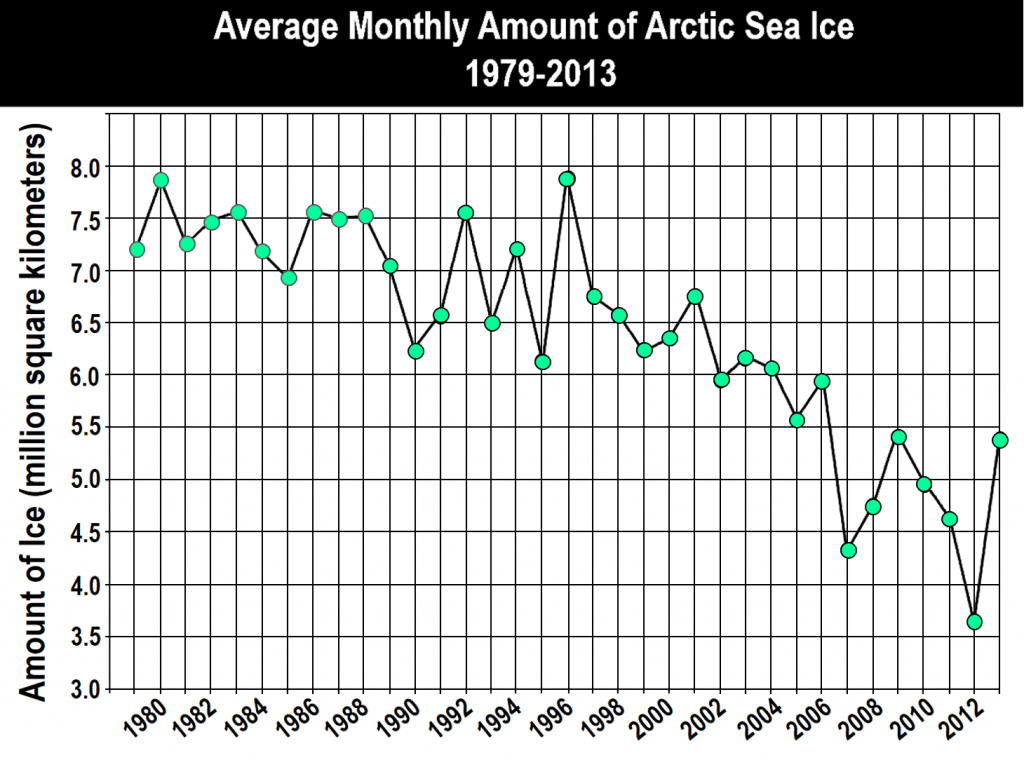

The Penn researchers had 2,400 Democrats and Republicans analyze a graph on Arctic sea ice levels, a climate change issue with surrounding opinions that are often separated by party lines.

After looking at the graphs, 26 percent of Democrats and 40 percent of Republicans incorrectly said the Arctic sea ice levels were increasing.

But when the participants were given time to interact anonymously on a social media platform without knowing each other’s party affiliation, 88 percent of Republicans and 86 percent of Democrats correctly agreed that sea ice levels were decreasing.

The participants who were not allowed to converse with each other on social media and instead had more personal time to think about their decision stuck to their polarized, often inaccurate ideas.

“Before our study, most people were blaming increasing polarization on cross-party discussions,” said Damon Centola, an associate professor in Penn’s Annenberg School for Communication and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and lead author of the study.

“In other words, scholars thought that exposure to opposing opinions was causing polarization,” he continued. “What we found was that the opposite is true. We found that bipartisan social media networks significantly increased consensus about climate change – leading over 85 percent of Republicans and Democrats to agree that Arctic sea ice is in fact decreasing.”

The study

To conduct the study, Centola, along with Penn doctoral student Douglas Guilbeault and recent Penn doctoral graduate Joshua Becker, created an experimental social media platform.

The researchers were inspired by the common misinterpretation of NASA’s 2013 graph on historical trends of sea ice. Despite the graph being relatively simple to interpret, many Americans were gathering incorrect information from the graph.

To test how interaction via social media would affect people’s interpretations of the graph, the researchers divided participants into 3 groups.

The first group, called the “political-identity setup,” revealed the political affiliation of each person.

The second group, called the “political-symbols setup,” attached a donkey or an elephant at the bottom of each person’s screen.

The final group, called the “non-political setup,” had participants interacting anonymously.

Each setup featured 20 Republicans and 20 Democrats.

Every participant was required to interpret the NASA graph for expected sea ice levels for 2025. They first had to answer on their own, but then they were allowed to view each other’s answers and make adjustments to their own.

Their findings revealed one of the main problems plaguing climate change communication and politics at large.

“Our results show that one of the main problems with communicating climate change is that even if you do get people to watch your program or listen to your new scientific information, they can nevertheless interpret in exactly the opposite way that you intended,” said Centola.

“Giving people information is not enough to change their minds. Partisan bias can still lead them to hold onto their old beliefs.”

A paper describing the full study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Why social media failed in the past

People may still be wary to rely on social media sites, which are largely responsible for the spread of fake news, to reduce political polarization.

But the new research suggests that social media holds great potential to shrink the polarization, if political imagery is set aside.

“The findings show that the cause of polarization is not cross-party communication, but rather communication in a politicized social context,” said Centola. “The presence of political imagery causes people to become entrenched in their partisan views.”

Unfortunately, political imagery has, to this point, always made a presence in social media spaces.

“It is always tempting to revert to familiar logos and icons, which can trigger an emotional reaction, and therefore increase engagement,” said Centola. “But, that engagement winds up being too polarized to be productive. A simple rule of thumb is that the more politicized the social setting is, the less likely that people will listen to each other.”

Improving social media

The researchers believe an effective way to improve cross-party communications would be to remove the political symbols and partisan logos from social media settings.

Removing people’s ability to fall back to the ideas of their “political camps” is key.

“This is also true for broadcast news programs in which people discuss climate change,” said Centola. “When symbols of partisan identity are removed from the screen, people become much more willing to learn from each other, and as a result they come to an informed consensus.”

What’s next?

The researchers are already working on developing a way to provide existing social media sites with more effective networking tools to connect people and create productive conversation and social learning, said Centola.

It is imperative to put people together “in the right way,” said Centola.

“If you can do this, then the natural human process of people learning from each other can take over,” he continued.

“In essence, the trick is to design spaces where we can get out of the way, and let people do what they do best, which is to work collectively to try to understand and improve their world.”