Billions of years before the invention of solar panels, algae was already harnessing the sun’s energy. Because algae has been optimized for light absorption through its evolution, the key to more efficient solar panels may be unlocked by working with algae.

That’s what a team of researchers from Yale University, Princeton University, Lincoln University and NASA banked on, and now the team has found a way to use algae to enhance organic solar panels.

The research was led by André Taylor, associate professor of chemical and environmental engineering at Yale, who runs the university’s Transformative Materials and Devices Laboratory.

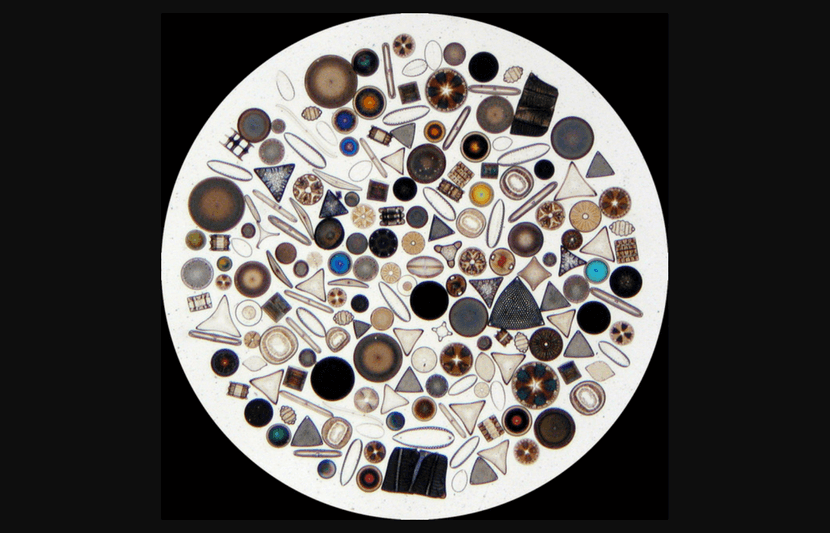

Jewels of the Sea

The species of algae being employed is known as a “diatom,” an extremely prolific strain that’s known as the “jewels of the sea.”

Diatoms are found in all types of water sources, and possess a skeleton made of nanostructured silica (glass). Due to its natural capacity for photosynthesis, diatomic algae is ideal for use in organic solar paneling.

Cheaper Alternative

When sunlight strikes an organic solar cell, electrons in the organic “active” layers pick up energy and begin moving that energy through the core of the solar panel.

The “active layer” materials currently used in solar cells are expensive and very rare. Diatom, on the other hand, is cheap and can be found almost anywhere. So figuring out how to harness diatom can help bring down the cost of organic solar panels.

To this end, the researchers worked with fossilized diatoms, which is also known as diatomaceous earth — a cheap, naturally recurring substance derived from dead algae.

Algae Nanostructures are Key

A common problem that occurs when manufacturing organic solar cells is that the active layers of organic material need to be thin, which both reduces their efficiency and can make it expensive to accomplish.

To solve this problem, the researchers developed a method for grinding the diatoms up into smaller bits, as the diatoms were initially too large to be placed in the active layer of the panel. They found that the electrical output levels stayed constant after their grinding method, even as the amount of material was reduced.

“We saw work by Jeremiah Toster et. al in Nanoscale where they implemented diatoms into dye sensitized solar cells and observed an enhanced power conversion efficiency,” said Lyndsey McMillon-Brown, a doctoral student in Taylor’s lab and co-lead author of the paper. “This sparked our interest as we were curious to see if diatoms could be successfully implemented into organic solar cells for an enhanced performance as well.”

What’s Next?

“We hope that this work will shed more light on the opportunity to utilize biomimicry or bio-inspired designs to solve engineering problems,” said McMillon-Brown. “Nature has developed many solutions that can be used to address many of our engineering problems – we just have to learn how to adapt and apply them.”

The researchers are keen on improving their technology and on finding a better-fitting strain of algae that they could use for higher performance.

“Moving forward we’re interested in optimizing the integration of diatomaceous earth into organic solar cells,” said McMillon-Brown. “In the future, we’d like to take care to select a species of diatoms that fit well into a high-performing polymer device.”

For more about this research, please see the paper published in Organic Electronics.

In addition to Taylor and McMillon-Brown, the study’s authors are Marina Mariano (co-lead author), YunHui L.Lin, Jinyang Li, Sara M. Hashmi, Andrey Semichaevsky and Barry P. Rand.