Artisanal brick kilns contribute significantly to pollution in developing nations. Fortunately, a team of researchers from Stanford University has come up with a novel way to reduce pollution from such brick kilns.

The team’s approach could have a major impact in mitigating global warming, improving air quality, and reducing negative health effects in adjoining communities.

Their creative, multi-pronged solution involves finding artisanal brick kilns from space, measuring negative health effects posed by these kilns, and incentivizing kiln owners to modernize the technology used for brick production.

Why is it important to tackle artisanal brick kilns?

Brick kilns are not bad per se. Modern technologies have made it possible to limit pollutant emissions during production. In modern kilns in China and developed countries like the U.S. and UK, for instance, the production process is highly automated. Bricks are made and pressed by machines and then fired in electricity-dependent tunnel kilns.

In contrast, artisanal brick kilns that are still used in parts of Asia and Latin America rely on human hands to shape the bricks. Workers mix topsoil, manure and other raw materials with water, press them into molds, and then lay them out to dry in the sun, which limits production to the dry season only. Then the sun-dried bricks are fired in kilns that use coal, biomass, tires, or other materials as fuel, which release carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, sulfur oxides, nitrogen dioxide, black carbon (soot), or other compounds into the air.

Alex Yu, a postdoctoral scholar in infectious disease at Stanford, paints a bleak picture of what he saw on the outskirts of Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh.

“There are chimney stacks everywhere pouring out black smog,” Yu said in a statement.

“You walk one block and your body is covered by a thin layer of soot.”

It’s not just the contaminated air that’s harmful. The land is also impacted when workers dig up topsoils for brick production, which in turn makes it harder for surrounding communities to grow crops and further compounds the problem of food insecurity.

What exactly is emitted and how much is emitted from these kilns depend on the type of kiln and fuel used, according to Ellen Baum, a senior scientist with Clean Air Task Force. There is no doubt though that emissions are harmful to the environment and the welfare of the communities surrounding these kilns.

Dr. Stephen Luby, a professor of medicine at Stanford, believes that the global warming impact caused by brick kilns across South Asia is equal to that of all passenger cars in the U.S. and that air pollution from these kilns kills tens of thousands of people each year as a result of respiratory and cardiovascular disease.

A World Bank Study, published in June 2011, also confirms the negative impact of artisanal brick kilns. According to the study, a cluster of 530 artisanal brick kilns in Dhaka is the primary source of emissions of particulate matter in the dry season — 38 percent, as compared to 19 percent for vehicular emissions. It is also estimated that the same cluster causes about 750 premature deaths from respiratory disease each year, which amounts to 20 percent of the total number of deaths in Dhaka that result from poor air quality.

These numbers speak to the effects from just 530 brick kilns in Dhaka, but there are approximately 8,000 of these kilns in Bangladesh.

The magnitude of the damage to the environment and to human health is immense when you factor in other such kilns in the world. For instance, India, which is the world’s largest artisanal producer of bricks, has over 100,000 of artisanal brick kilns. Latin America has fewer of these kilns, but they are still significant in number — about 300 in Chile, between 8,000 and 10,000 in Peru, and about 17,000 in Mexico, for example — so action is still needed to mitigate the problem.

Many organizations, including The Climate and Clean Air Coalition to Reduce Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (CCAC), have introduced initiatives to modernize artisanal brick kilns.

One of the major problems they face, however, is that it is not easy to get an accurate count of the number of these kilns within specific areas, as these kilns are often not registered with relevant authorities.

According to an article published in Environmental Health Perspectives, when a Swiss-funded group known as EELA (Eficiencia Energé- tica en Ladrilleras Artesanales) was formed in 2010 with the aim to modernize artisanal brick kilns in Peru, Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Mexico, they couldn’t get accurate counts of the kilns from either governments or local authorities.

In Cusco, Peru, for example, the number given by authorities was way off.

“They told us three to five kilns, but that was only the formal, registered enterprises,” Jon Bickel, a Swiss development expert based in Lima, told the article’s author. “We had to go door to door to find out the true number, which was closer to three hundred.”

Luby’s vision inspires collaborative, multi-pronged solution

Having an accurate count will no longer pose a problem to modernization efforts now that the Stanford researchers have a unique solution — using satellite images to map the locations of artisanal brick kilns.

Luby was instrumental for the team’s aerial solution.

“I first had the idea for using satellite images when I was flying over India in August 2014,” he said.

“The plane was descending, so we were getting closer to the ground. I had been working on brick kilns for a couple of years at that point and so I started noticing them by looking out the plane window, and recognized that I could even make distinctions between different kiln designs. I thought if I could detect kiln sitting on a plane, that we should be able to identify them by remote sensing.”

Luby immediately sought out the right colleagues to help him realize his vision. He found one in Howard Zebke, a professor of electrical engineering and geophysics at Stanford, who is an expert on developing space-borne radar systems and using remote sensing data to study earthquakes, volcanoes, polar ice movements, and other phenomena.

He also found one in Francis Fukuyama, a senior fellow at the university’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, who helps the team understand applicable governance issues in countries or regions where these kilns are located and develop a message that will resonate within the affected community.

The message includes the launch of a public website that would allow people to learn about kilns in their area and the methods to urge kiln owners to modernize their operations. People could also use the website to flag kilns that are in violation of local ordinances or other standards, and to engage in discussions with other public and private sector stakeholders.

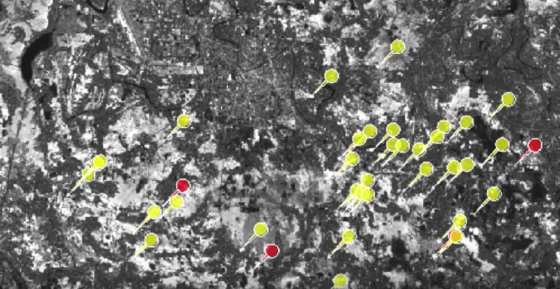

The team relies on data from the Sentinel 1 satellite launched by the European Space Agency in 2015 to map the locations of the kilns.

Abhilash Sunder Raj, an electrical engineering graduate student at the university, has used the data and GPS locations of kilns found by ground teams to create a model that can distinguish kilns from non-kilns from space. The model works so accurately that it found kilns missed by ground teams.

“We are able to find these needles in a haystack very, very accurately,” Sunder Raj said in a statement.

The team’s solution also includes measuring the negative health effects of artisanal brick kilns. Yu’s task is to determine if there are other pollution sources that affect health so much that the health issues would continue even if brick kilns were less polluting. To do that, he is comparing relevant data from villages with and without kilns, including rates of asthma, pneumonia and carbon monoxide.

The researchers have teamed up with Greentech Knowledge Solutions, a company based in Delhi, India with experience in improving brick kiln efficiency, to resolve the kiln situation in Bangladesh first.

“Our initial efforts toward sector transformation will be focused on Bangladesh, but because this is a problem across South Asia I anticipate that a successful model is likely to be taken up and copied,” said Luby.

Changes won’t come easy

Many factors stand in the way of convincing brick kiln owners to modernize their operations, but Luby believes that the team can overcome these obstacles.

“I anticipate that the three biggest constraints will be lack of knowledge, lack of capital and a reluctance to change from a model that is well understood and profitable,” said Luby.

“I believe working with Greentech, our Indian technical colleagues, and getting more experience in the field will help us to generate the knowledge, and we can use this to overcome the knowledge constraint of kiln owners. Many kiln owners are short on capital, but I believe this constraint can be overcome by impact investors who would be willing to lend the capital in order to reduce pollution and improve health as long as they get their investment back with reasonable interest. Because the improvements we are targeting also improve fuel efficiency, this would lower the cost of coal for kiln owners and so there is a sufficient revenue stream to pay back investors. I believe we can overcome the reluctance to change, through combined encouragement from affected communities and from government regulatory authorities.”

The team’s efforts in this regard include finding out from brick kiln owners the obstacles they face in modernizing their operations and researching the best ways to motivate the stakeholders in Bangladesh and effect behavioral change. Fukuyama will apply that knowledge to the policy reform training program he has in place for mid-career government officials in developing countries.

Luby and his team have taken on an immense project, which will take some time to accomplish.

When asked as to how long it would take, Luby’s response was: “More than five years, but I hope less than 20.”

His prediction is based on his personal experience in South Asia.

“My experience working in South Asia is that change is possible, but it requires persistence,” he said. “I lived in Bangladesh for eight years and have been working there for 15 years.”

Conclusion

Tackling pollution from artisanal brick kilns is critical for both the environment and the welfare of millions of people around them.

“Humanity’s future depends upon a healthy environment,” said Luby.

“We cannot afford to continue rewarding businesses that earn money by destroying the environment and destroying health. These are perverse incentives. I consider this work important, both because of the damage to the environment and the damage to human health that these brick kilns generate. More generally, it is important that we develop examples of successful interventions to counter perverse incentives.”