Australia’s Great Barrier Reef stretches over hundreds of thousands of square miles, encompassing a vibrant ecosystem of brightly colored corals and a vast pool of marine life.

But, a recent study found that 30 percent of its corals died during a nine-month heat wave from March to November 2016.

This discovery highlights the continuing threat to coral reefs around the world. In the past 30 years alone, over 50 percent of the world’s coral reefs have died.

Warming waters, pollution and overfishing are just a few of the many factors affecting these unique ecosystems.

Fortunately, many researchers, ecologists and activists from around the world have drawn on their resources to help conserve and restore these vital structures.

The importance of coral reefs

Coral reefs cover less than one percent of the ocean floor, but they have long been considered to be one of the most valuable ecosystems on earth.

These important structures support more species per unit than any other existing marine environment, including one-fourth of the world’s fish, and 30 percent of total marine biodiversity. Species such as corals, clams, lobsters, sea horses, sponges and sea turtles are just a few of the many creatures that rely on coral reefs for survival.

But marine species aren’t the only ones that depend on coral reefs for their livelihood.

Approximately 500 million people worldwide rely on coral reefs for food and income, with 30 million people almost completely dependent on reefs, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Coral reefs provide income to coastal communities through fishing, recreation and tourism, and serve as an important source of food and coastline protection for millions of people annually.

Additionally, coral reefs contribute billions of dollars to world economies each year.

It is not surprising then that their continued degradation will have significant ecological, economic and cultural impact on people and places around the world.

“Many people’s livelihoods depend heavily on fisheries, tourism, and coastal protection, which are all provided by healthy coral reefs,” said Aric Bickel, project and workshop manager at SECORE International, a leading organization for the protection and restoration of coral reefs. “If we want to keep the important ecological and economic services coral reefs are providing, we need to protect and restore the reefs.”

Unfortunately, coral reefs face persistent threats and losses.

Scientists project that at the current rate of degradation, 90 percent of all coral reefs will be highly threatened by 2030.

What’s killing coral reefs?

Increasingly, coral reefs are subject to stress from rising sea temperatures, pollution, invasive fishing, careless tourism, and natural phenomena.

However, according to NOAA, the top three threats to coral reefs — climate change, unsustainable fishing, and land-based pollution — are all due to human activity.

Of these three, perhaps the biggest threat to coral reefs comes from rising sea temperatures.

Though coral reefs can withstand providing food, shelter and other resources to thousands of creatures, they are actually quite sensitive structures, particularly when it comes to heat.

For a reef system to form, coral larvae first attaches itself to coastal rocks or soil. The larvae then grows into coral polyps, or tiny animals that excrete calcium carbonate to build an exoskeleton.

During this time, coral polyps develop a symbiotic relationship with algae, which helps them grow. As they grow, they excrete more calcium carbonate, allowing more and more coral polyps to attach to the surface, and eventually, a coral reef is formed.

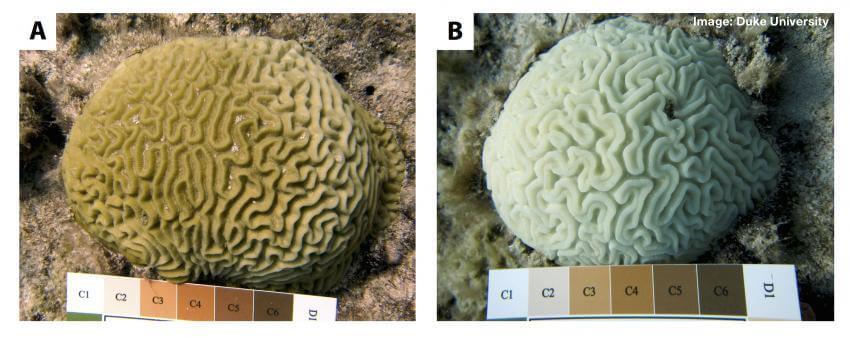

But, when water near a reef gets overheated, the coral algae begins producing toxins and the corals expel them from their tissue in self-defense. Known as coral bleaching, this process turns the corals a ghostly white, leaving them stressed and vulnerable to starvation or disease.

“If corals are stressed, one of the first things that happens is that they stop reproduction. They just don’t have the energy available to produce all these gametes, eggs and sperm, because they are trying to survive,” said Bickel.

But a bleaching event doesn’t necessarily mean a coral reef will die. If water temperatures drop quickly enough, corals can heal themselves by growing new algae.

Unfortunately, for many reefs, this opportunity never arrives.

Due to increasingly warm oceans, coral bleachings have become five times more common worldwide than they were just 40 years ago.

Effects of climate change

Globally, the ocean has warmed by about 1.6 degrees Fahrenheit during the past 100 years, according to the NOAA.

In addition, from 2014 to 2017, increasing sea temperatures by an El Niño weather pattern resulted in the longest, most widespread, and most damaging bleaching event to date.

The event was so bad that in 2016, scientists reported 93 percent of the Great Barrier Reef to be bleached.

Since then, mass bleachings have been documented in the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Caribbean, Australia, Hawaii, and Florida Keys — a reality that has serious implications for the planet.

Aside from causing damage to the many species reliant on reefs for food and shelter, coral bleaching can result in the stunted growth of reefs, a problem that will severely impact coastal communities.

According to a new study by The University of Exeter in the UK, bleaching in the Caribbean and Indian Oceans has affected the rates of coral growth to the point where soon, many reefs will be unable to keep up with rising sea levels.

Among other reasons, this is problematic for coastal communities because coral reefs often provide a natural barrier against erosion and flooding.

“Average vertical reef growth rates across the Indian Ocean and Caribbean regions are around 2 mm per year at present but projections of even quite modest sea-level rise average around 6 mm per year,” said Chris Perry, a professor of physical geography at the University of Exeter.

“As a result, there is an increasing divergence between the two and this will start to reduce the ability of reefs to limit coastal wave exposure — with obvious increasing threats to coastal communities from shoreline erosion and flooding,” he continued.

Unless urgent actions to drive forward reductions in CO2 emissions are initiated by 2100, Perry fears that the inundation of reefs will significantly threaten coastal communities.

“In essence what is needed is a combination of both global (political) action on CO2 emissions – this is important because it contributes to warming that can impact reefs via bleaching events and because it drives the sea-level rise side of the problem, and we need to see local actions to protect reefs and reduce the effects of local stressors like poor water quality (from sewage etc.),” he said.

What can be done to save corals?

With the severity of coral reef degradation at the forefront of many scientific minds, numerous coral restoration approaches have been taken.

Large-scale restoration approach

One method that has gained popularity in recent years has to do with the sexual reproduction capabilities of coral reefs.

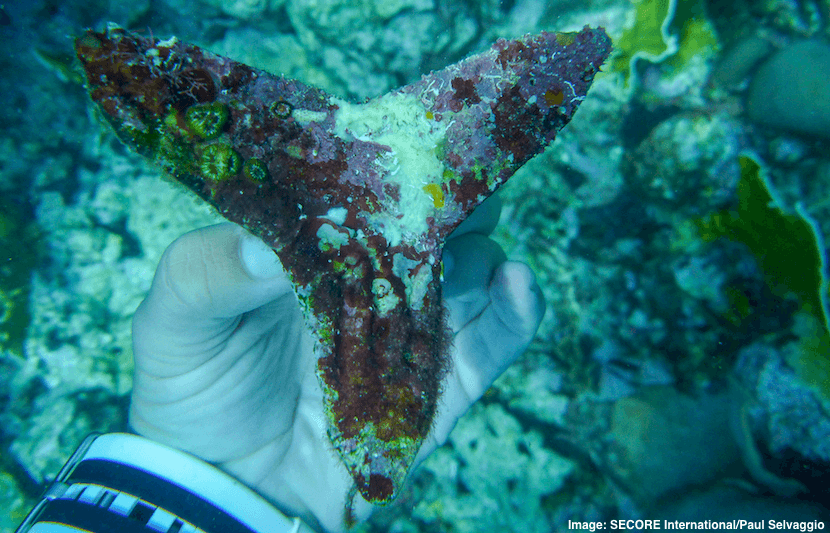

In collaboration with a network of international researchers, SECORE has developed a sexual restoration “sowing” approach that could be used for large-scale efforts.

The idea behind this approach is to collect massive amounts of coral larvae during a spawning period and attach them to specifically designed “tetrapod” substrates that can wedge themselves between the crevices of reefs.

Once the larvae turns into initial coral polyps, the researchers can drop the substrates from boats onto degraded reefs, like famers scattering seedlings on a field.

“By designing substrates (we call them seeding units) that are self-settling and can be sown from a boat or through other methods (similar to how a farmer sows seeds), we can eliminate much of the human labor needed and greatly reduce the final cost of each coral outplanted,” said Bickel.

Compared to manual restoration efforts initiated by sea-divers, which require several hundred to a few thousand person-hours, this method could be achieved in fewer than 50 person-hours, making it 90 percent more efficient to restore reefs.

“If we want restoration to play a more meaningful role in coral reef conservation, we need to think in new directions,” said Bickel. “Our sowing approach is an important step towards reaching this goal since it will allow the handling of large numbers of corals in a very short amount of time at significantly lower costs.”

Additionally, this sowing process allows the researchers to promote genetic diversity, which is essential to prepare future reefs for increasing sea temperatures, he explained.

So far, the research has been tested on reefs in Curaçao, Mexico, the Bahamas, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Philippines.

SECORE has partnered with the California Academy of Sciences and the Nature Conservancy to further its aims to output one million corals by 2021, as a part of their goal with The Global Coral Restoration Project.

A “mixed” restoration approach

While Bickel explained that the sowing approach could be initiated on a global scale, he emphasized that there is no “silver bullet” for restoring coral reefs.

In other words, all reefs are different, so not all reefs will require the same restoration methods — some might need a mix of restoration approaches, while others might not.

Building on this idea, researchers from The University of California Santa Barbara have advocated for the integration of unique natural processes and ecological forces to drive restoration efforts.

Inspired by a meeting of restoration experts from around the Caribbean led by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the researchers outlined a scientific framework to help improve restoration by drawing on decades of coral reef ecology research.

They ultimately proposed that scientists must look into the specific context-dependent ecological qualities of the reefs they’re working with in order to conduct efficient and appropriate restoration practices.

“Recognizing that ecological processes play an important, yet underappreciated role in coral restoration, the framework we propose is a combination of input, survey results, and lessons learned from these and other coral restoration practitioners,” said Mark Ladd, a doctoral student at UC Santa Barbara, who led the research.

The researchers determined that restoration practitioners can control factors such as the density, diversity and identity of transplanted corals, as well as the site selection and transplant design, to restore positive feedback processes.

“It is essential that we have a firm understanding of the important processes that shape coral reef communities to be able to effectively incorporate and promote positive processes – or reduce negative ones – to make coral restoration more successful,” said Ladd.

This research solidifies the importance of understanding the functions and practices of each unique coral reef ecosystem before initiating a restoration effort.

Local approach

Many research teams have also initiated smaller, more localized efforts to help coral reefs.

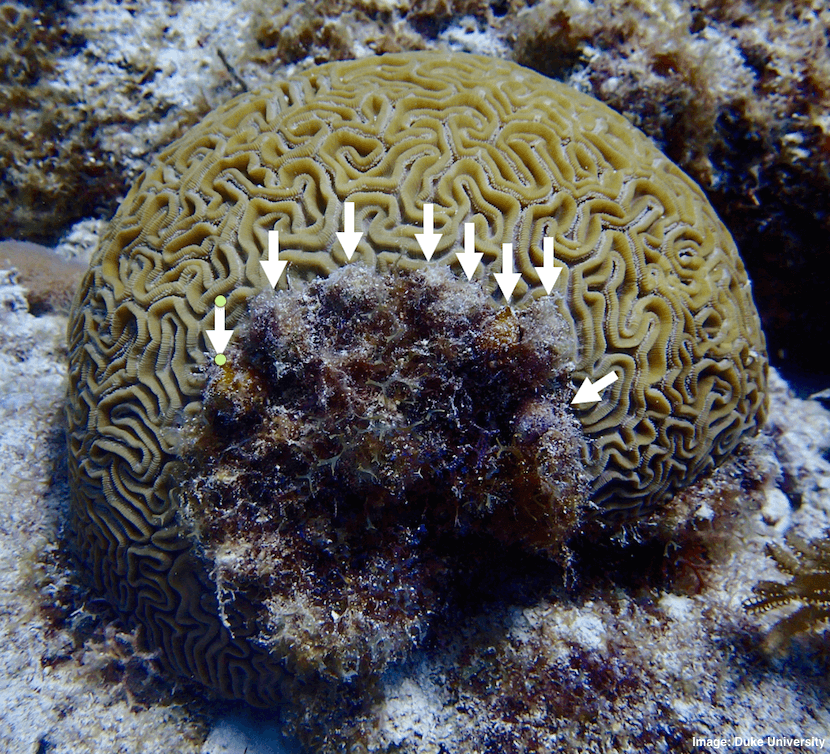

For example, a recent report by Duke University showed that local efforts, such as protecting coral reefs from predators, can significantly boost corals resilience to bleaching.

In this study, the researchers focused their efforts on brain corals found in the Florida Keys, which are known to be highly susceptible to predation by snails.

In 2014, during a three-month spike in ocean temperatures, the researchers went down to the Keys and physically removed snails from some brain coral sites. Their idea was to see if removing predators could help corals withstand and recover from warmer temperatures, and therefore, decrease bleaching.

And it worked.

When the researchers returned to the reefs after water temperatures cooled down, they found that the corals with less snails experienced only 50 percent bleaching, while the corals with a high density of snails experienced nearly 100 percent bleaching.

“Our findings suggest that local conservation efforts can play an important role in helping conserve coral reefs in addition to large-scale, global efforts to mitigate or stop climate change,” said Elizabeth Shaver, a 2018 doctoral graduate of Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, who is now a coral restoration scientist with The Nature Conservancy’s Reef Resilience Program.

Shaver suggests that there are likely several other interventions that can be initiated at a local level to help protect coral reefs from warm temperatures.

“Nutrient pollution and overfishing of herbivorous parrotfish are common local threats to coral reefs, and both of these threats can increase coral bleaching during warm temperature events. We need to test whether removing these threats can also help corals be more resilient,” she said.

The researchers re-open the discussion of initiating localized efforts at a time when people are increasingly saying that local actions aren’t making enough of a difference, and that more money should be put into global efforts.

“Our research highlights the need for more experiments to be done to test other local management actions that can help corals be more resilient to climate change and help buy them time since climate change action is likely to be a long and difficult process,” said Shaver.

Conclusion

“There is an urgent need to develop effective strategies to restore corals and the invaluable services they provide,” said Ladd.

Fortunately, SECORE researchers predict that coral restoration efforts will likely become as commonly applied as reforestation and help to change the landscape of future reefs as best they can.

However, Bickel added that restoration alone will not solve the coral reef crisis.

Instead, researchers from around the world believe that coral reefs will not withstand life for much longer unless global efforts are initiated to fight climate change.

Until then, restoration is our best hope.

“Restoring these services should be our focus,” said Bickel. “Nonetheless, coral restoration can only buy us some time. Time that we must use to solve the greatest challenge of our time — global climate change.”