In October 2010, government leaders from all over the world gathered for the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in Nagoya, Japan, and committed to reach sustainability targets by 2020.

Now, eight years later, researchers warn that the current global progress toward sustainability goals is not fast enough to avert the biodiversity crisis, especially in the world’s oceans and seas.

According to a research team led by the California Academy of Sciences, a research center focused on nature and sustainability of life on Earth, most signatory countries are not on track to achieve target goals, some of which are actually structured to falsely look like they have been achieved.

“After reviewing the commitments of several nations we have visited, we knew that the proposed goals were very ambitious,” said Hudson Pinheiro, an Academy postdoctoral researcher and the lead author of the study.

His team has concluded that these targets must be restructured to incorporate adequate conservation incentives that instill valid hope for the future.

“We want policy leaders to recognize that some targets need to be reassessed and improved in order to optimize the sustainability of the world’s marine ecosystems and make real progress towards averting the biodiversity crisis,” Pinheiro said in a statement.

Image: © Felipe Buloto

The study is published in Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation.

The study

Out of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the Paris Accords and the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets, the team assessed goals that specifically aim to conserve and sustainably use the oceans and marine resources.

These goals are continually promoted by the UN CBD and signatory countries, which most recently convened in Egypt last month.

Even though nothing has really changed, the team found that some of signatory countries present a false sense of achievement.

For example, Target 11 of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets requires signatory countries to protect 10 percent of the ocean by 2020. However, in order to look like they’ve met the target, many countries were actually protecting large expanses of ocean that are low-conflict and of little biological diversity without focusing on coastal regions that are most in need.

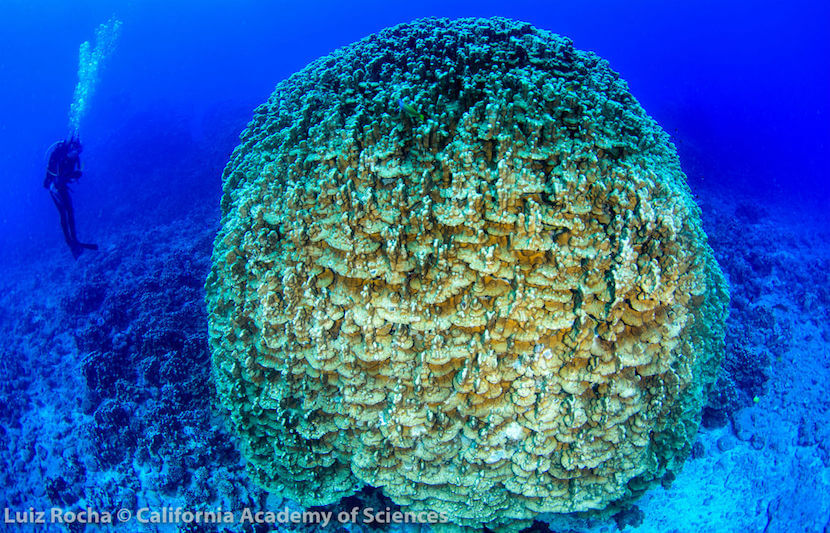

“Near-shore waters have a greater diversity of species and face more immediate threats from energy extraction, tourism, development, habitat degradation and overfishing,” Luiz Rocha, an Academy co-leader of the Hope for Reefs initiative, said in a statement.

In a New York Times op-ed last year, Rocha argued that the establishment of a large, open ocean as protected areas in Brazil, before securing coastal areas, was well-intentioned but significantly flawed.

“If we leave these highly vulnerable and biodiverse places at risk, we’re not really accomplishing the goal of protecting the seas,” he wrote.

Also, in order to meet some sustainability targets that aim to minimize the impacts of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems by slowing greenhouse gas emissions, many countries stopped consuming fossil fuels and have turned their focus to expanding “clean” energy sectors, like hydroelectricity. However, the team found that these sectors still depend on environmentally polluting practices.

Image: © Eric Mazzei

After the assessment, the team presented challenges and recommendations related to the following areas of conservation priority: marine protected areas, coastal ecosystem management, overfishing, marine pollution and ocean acidification.

For example, to dissuade countries from protecting large swathes of ocean habitat that favor low-conflict, low-diversity areas, the team recommends dropping the numerical target of protecting 10 percent of a country’s marine territory. Instead, countries should focus on protecting the highest number of species and ecosystem types to better align with end conservation goals.

Starting small

Although national governments may not measure up to their promises, the team encourages individuals to commit to change. They can encourage, or keep, industry leaders and local governments accountable to promote policies that further conserve the oceans.

For example, when the federal government refused to commit to the Paris Accords last year, the Academy became the first major museum to commit. The state of California and the city of São Paulo are also advancing at a much faster pace to reaching targets than their home countries, United States and Brazil.

College students should get involved as well.

“College students are our future leaders who will spread the word, and their actions help build a more sustainable future,” said Pinheiro.

Students can start making changes right from their campus towns, he points out.

“Supporting and participating in activities from local non-governmental organizations is an easy way to start,” he said. “Many organizations coordinate movements to clean up beaches, parks and natural areas, promote local fishing and produce, and organize outreach activities.”

If nothing else, all of us can contribute by taking a few more minutes to recycle properly or choose sustainable seafood.

What’s next?

According to Pinheiro, the team plans to continue with their Hope for Reefs initiative, which aims to explore, explain and sustain life on the world’s coral reef ecosystem.

Image: Luiz Rocha © California Academy of Sciences

“Knowing more about nature and how society consumes resources allows us to propose projects for sustainable development and conservation,” he said.